Michael Hudson

… and forgive them their debts: Lending, Foreclosure and Redemption from Bronze Age Finance to the Jubilee Year

© 2018

© Michael Hudson

© ISLET-Verlag Dresden

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means without written permission of the publisher, except for brief quotations in critical reviews or noncommercial uses as permitted by copyright law when credit is given.

eBook set in Palatino Linotype that includes foreign and ancient language diacritics.

Schriftsatz: Cornelia Wunsch

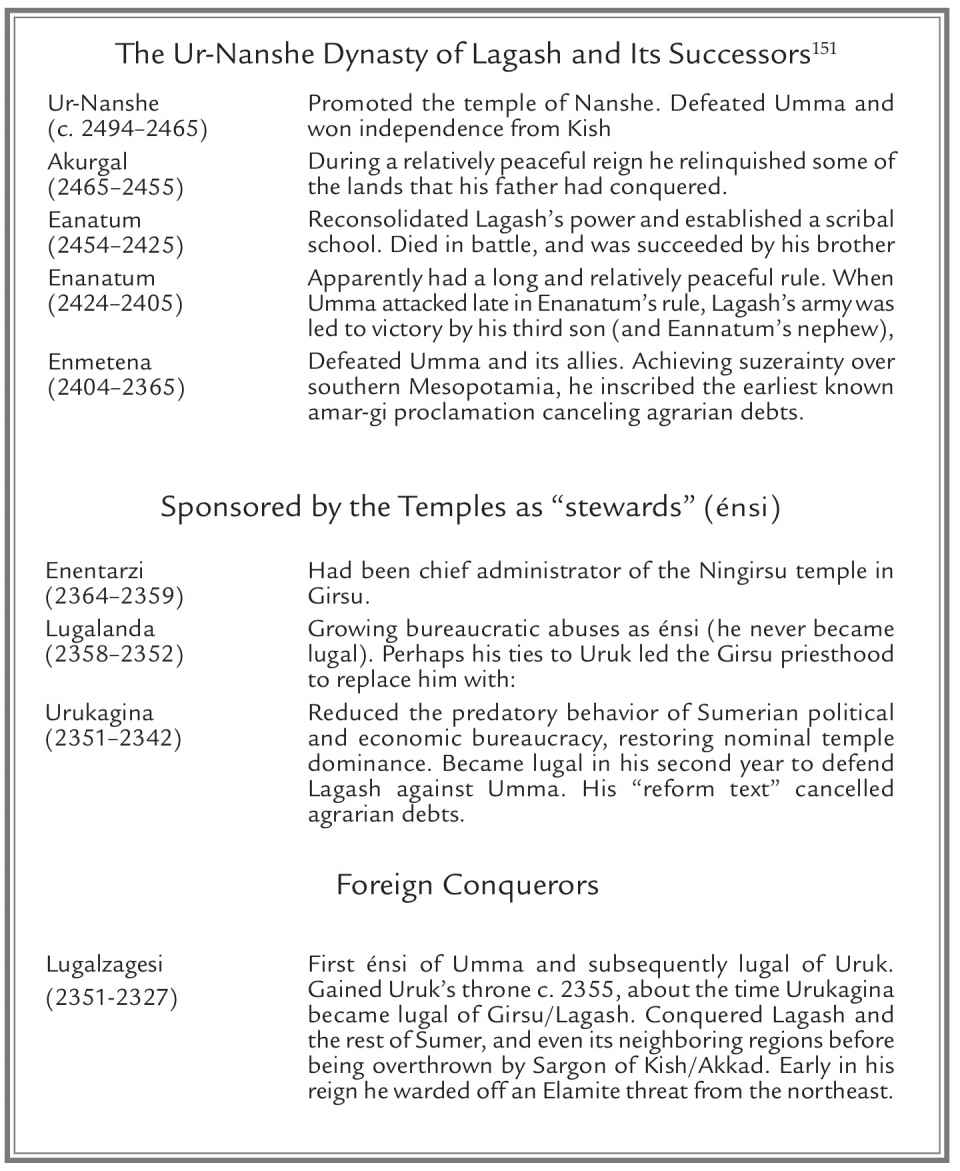

Cover design: Miguel Guerra, 7robots.com

eBook: Lynn Yost (V270319)

ISBN

To Carl Lamberg-Karlovsky

my mentor at Harvard’s

Peabody Museum

since 1984

Table of Contents

The Rise and Fall of Jubilee Debt Cancellations and Clean Slates

Social purpose of Debt Jubilees

How well did Debt Jubilees succeed?

Why did debt Jubilees fall into disuse?

Archaic Economies versus Modern Preconceptions

Widespread misinterpretation of Neolithic and Bronze Age society

The International Scholars Conference on Ancient Near Eastern Economies (ISCANEE)

What makes Western civilization “Western”?

A legacy of financial instability

1. Babylonian Perspective on Liberty and Economic Order

2. Jesus’s First Sermon and the Tradition of Debt Amnesty 32-57

The meaning of Biblical deror (and hence “the Year of Our Lord”)

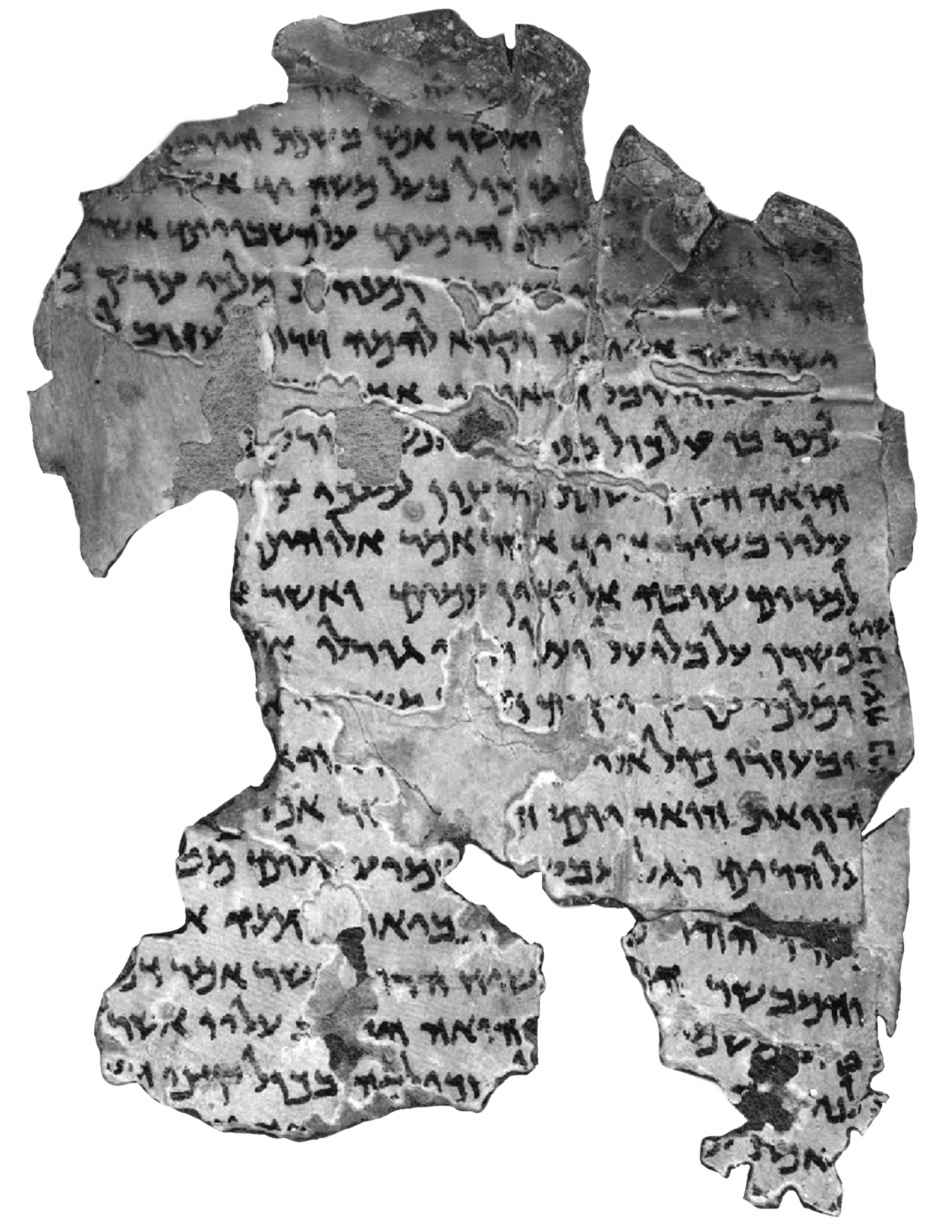

The Dead Sea Scroll 11QMelchizedek

Debt in the Biblical laws, historical narratives and parables

3. Credit, Debt and Money: Their Social and Private Contexts

From chieftain households to temples

Anachronistic views of the Mesopotamian takeoff and its enterprise

Growing scale of the temple and palace economy leads to monetization

Creating markets for commodities, and as a fiscal vehicle for tax debts

What Sumerian commercial enterprise bequeathed to antiquity

Classical antiquity privatizes credit and stops cancelling agrarian debts

How the modern financial and legal system emerged from antiquity’s debt crisis

A Chronology of Clean Slates and Debt Revolts in Antiquity

Mesopotamian Debt Cancellations, 2400–1600 BC

Allusions to Debt Cancellations in Canaan/Israel/Judah and Egypt 1400–131 BC

Debt Crises in Classical Antiquity: Greece and Rome 650 BC–425 AD

Part II: Social Origins of Debt

4. The Anthropology of Debt, from Gift Exchange to Wergild Fines

Fine-debts for personal injury catalyze special-purpose proto-money

Cattle as a denominator of debts, but not of commercial exchange or interest

Debt collection procedures originally preserved economic viability

5. Creditors as Predators: The Anthropology of Usury

Failure of physical productivity or risk levels to explain early interest rates

Most personal loans are for consumption, not to make a profit

Paying interest out of the surplus provided by the debtor’s own collateral

The polarizing dynamics of agrarian usury, contrasted with productive credit

6. Origins of Mercantile Interest in Sumer’s Palaces and Temples

How the social values of tribal communities discourage enterprise

Temples of enterprise

The need for merchants and other commercial agents to manage trade

The primary role of the large institutions in setting interest rates

Nullification of commercial silver debts when accidents prevented payment

7. Rural Usury as a Lever to Privatize Land

How debt bondage interfered with royal claims for corvée labor

Fictive “adoptions” to circumvent sanctions against alienating land to outsiders

Royal proclamations to save rural debtors from disenfranchisement

Part III: The Bronze Age Invents Usury, But Counters Its Adverse Effects

8. War, Debt and amar-gi in Sumer, 2400 BC

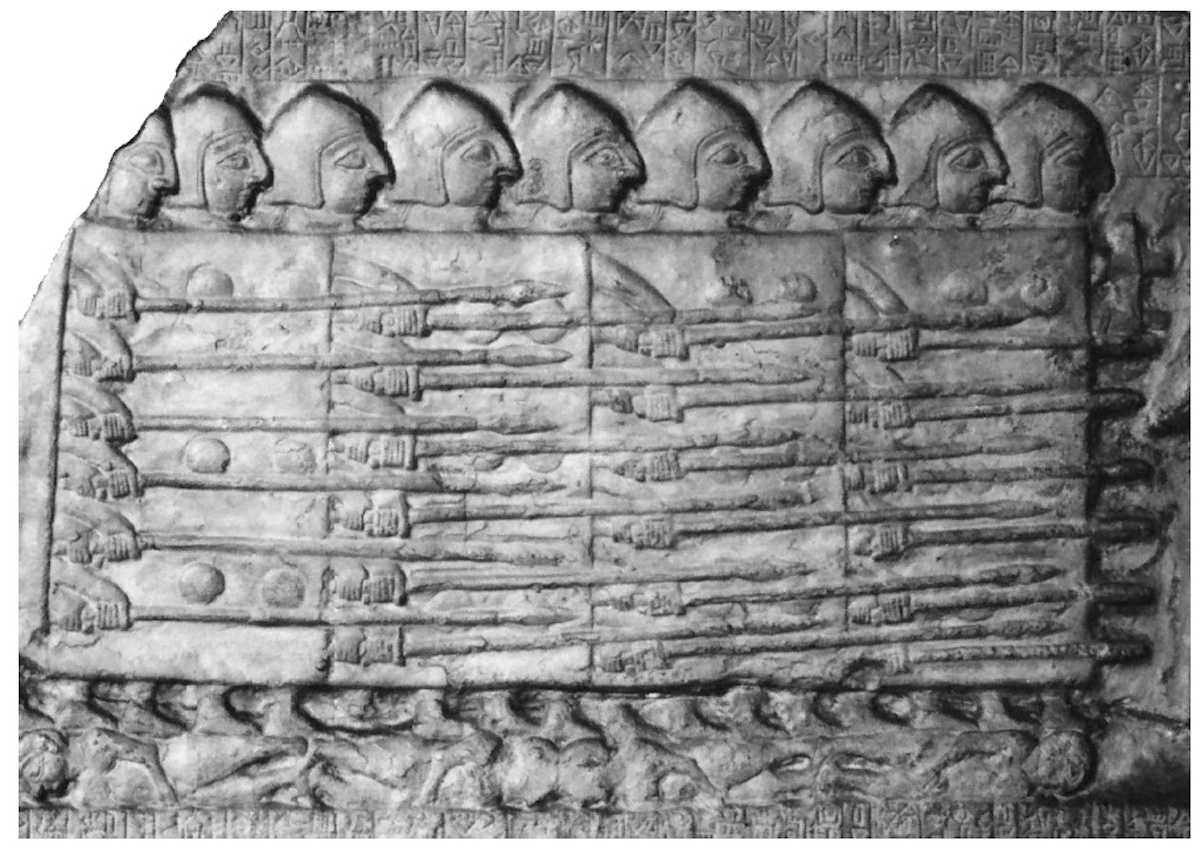

Lagash’s water wars with Umma, and the ensuing tribute debts

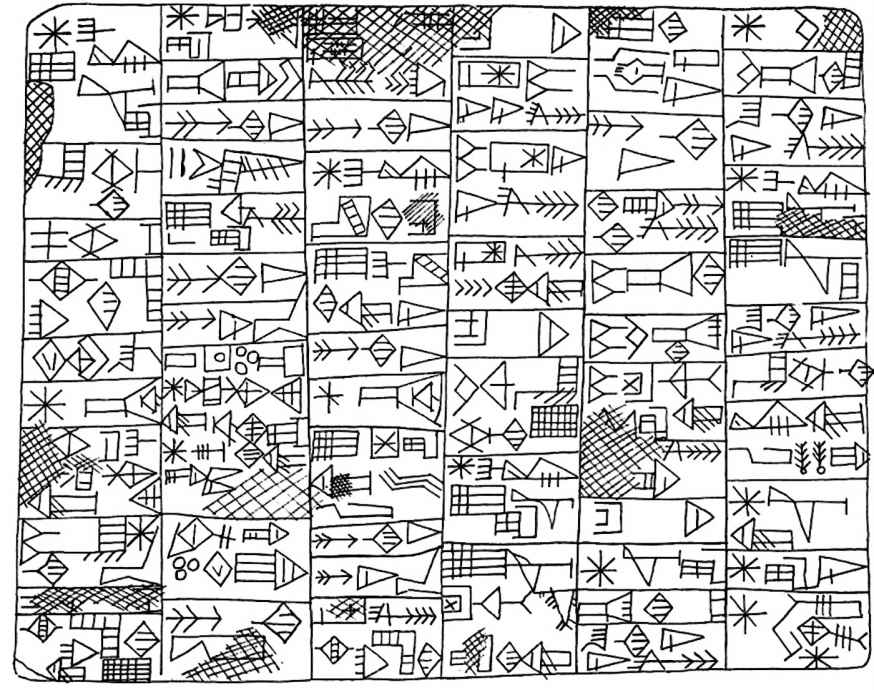

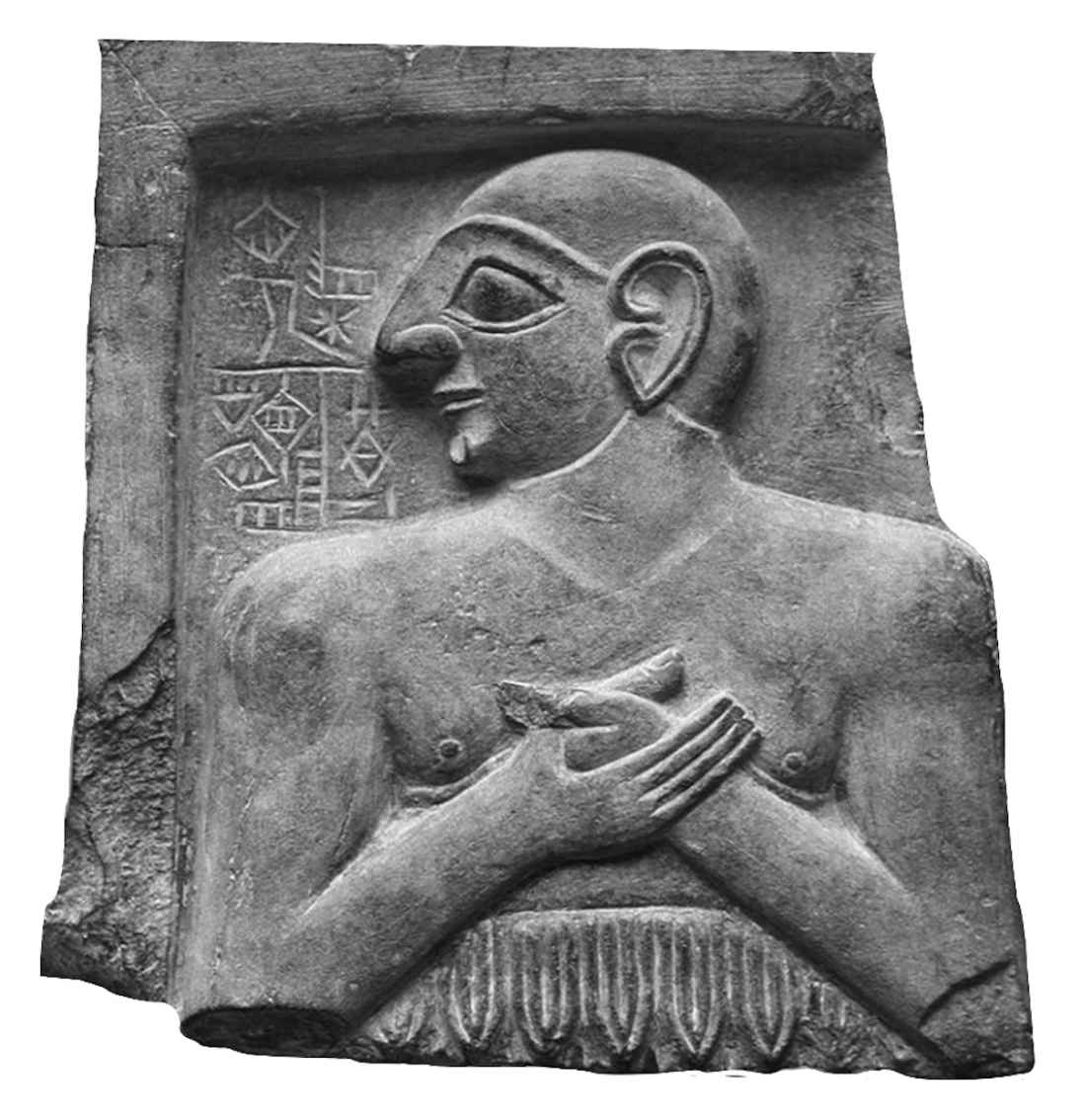

Enmetena’s proclamation of amar-gi, economic freedom from debt

9. Urukagina Proclaims amar-gi: 2350 BC

Sumerian amar-gi as an ideological Rorschach test for translators

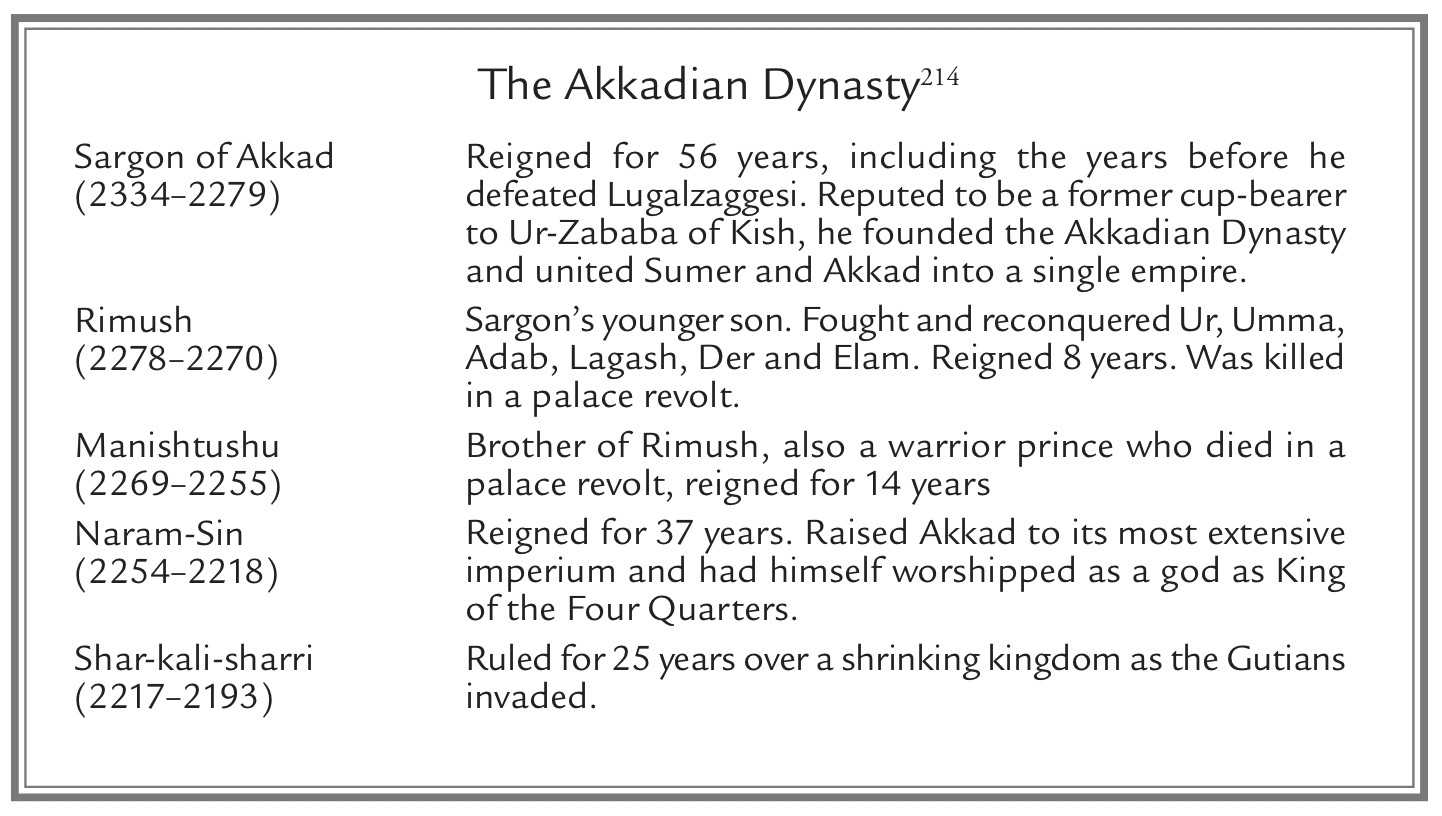

10. Sargon’s Akkadian Empire and Its Collapse, 2300–2100 BC

Descent of the Gutians into Mesopotamia, and the First Interregnum

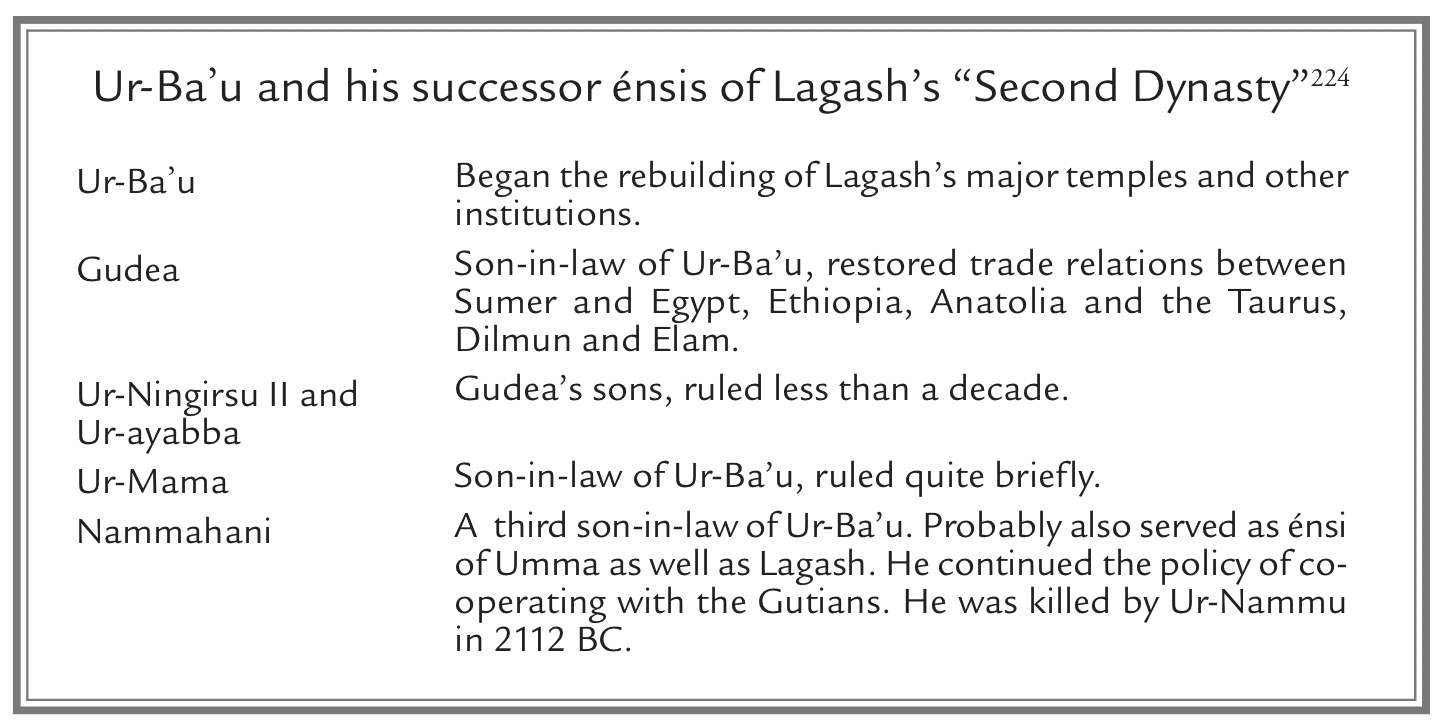

11. Lagash’s Revival Under Gudea, and his Debt Cancellation, 2130 BC

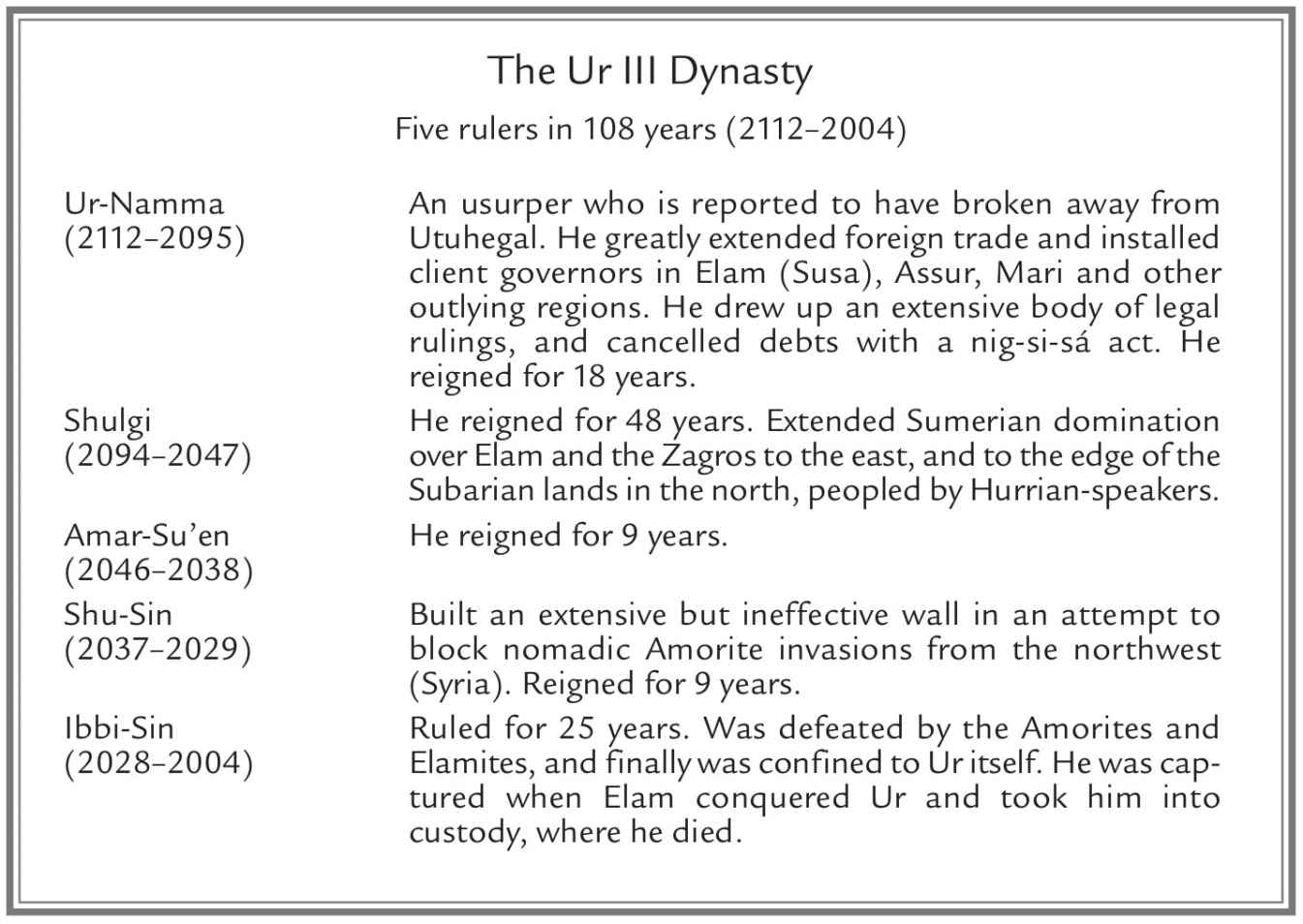

12. Trade, Enterprise and Debt in Ur III: 2111–2004 BC

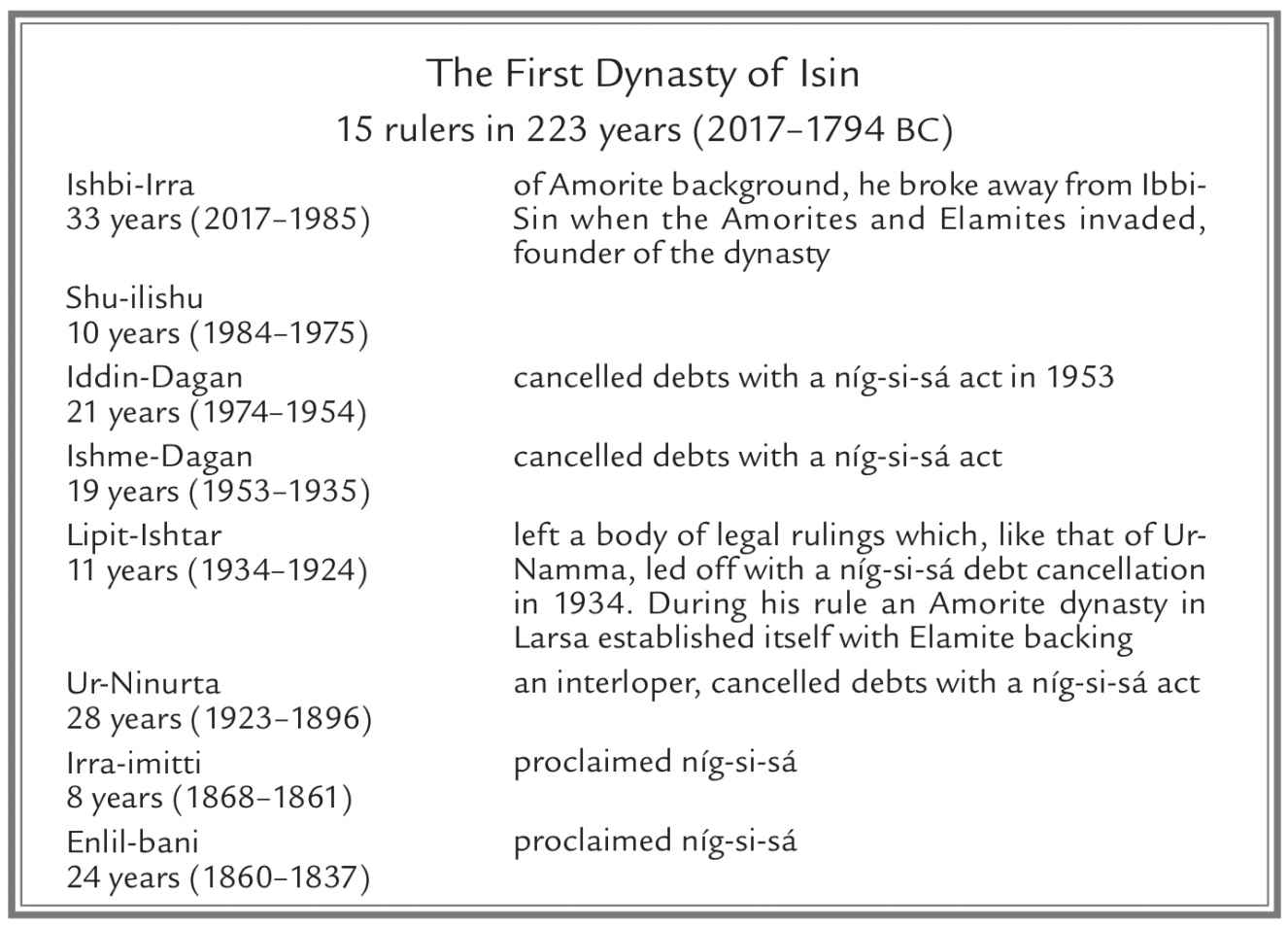

13. Isin Rulers replace Ur III and Proclaim níg-si-sá: 2017–1861 BC

14. Diffusion of Trade and Finance Via Assyrian Merchants, 2000–1790 BC

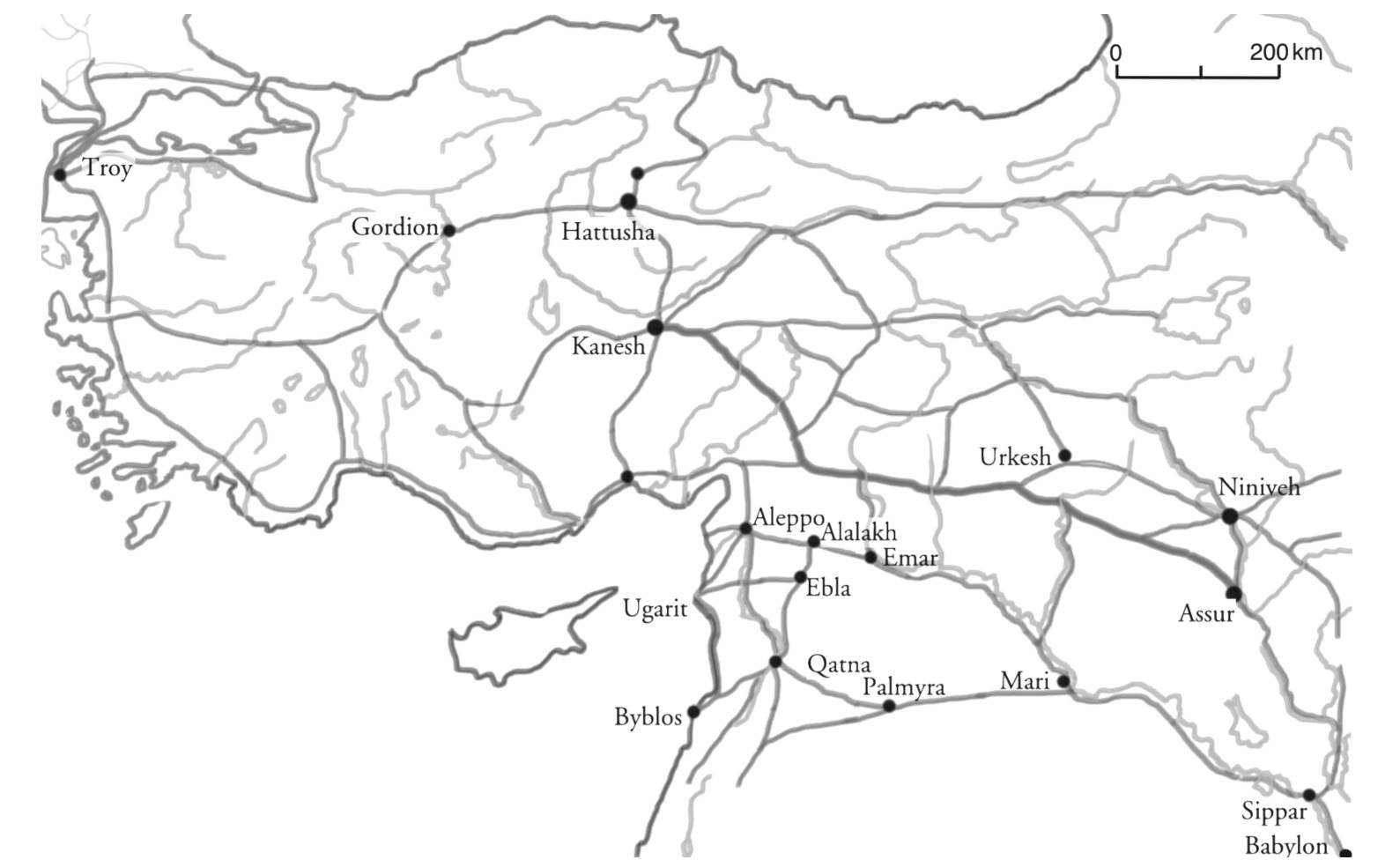

The archaeological context for Assur’s andurārum inscriptions

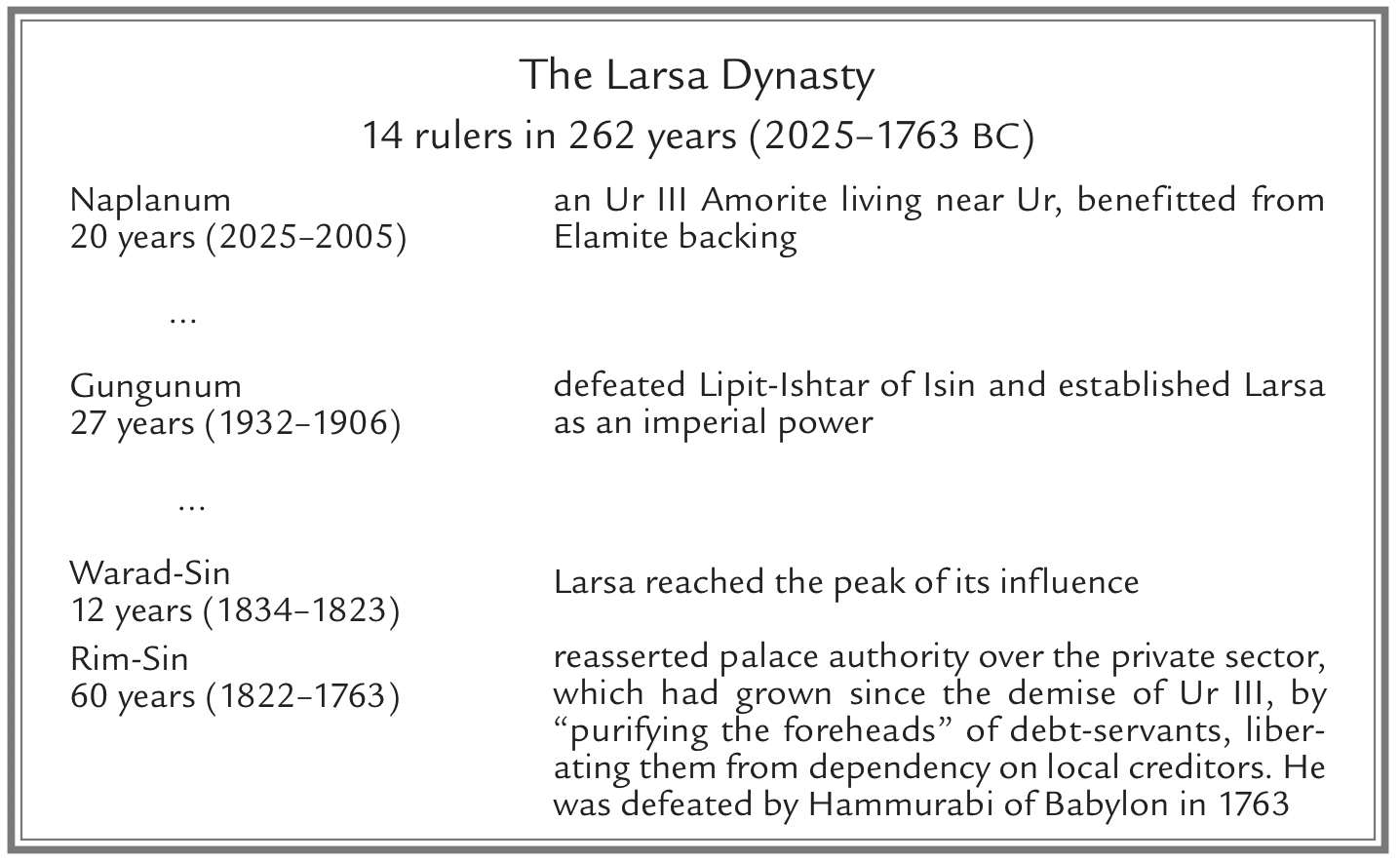

15. Privatizing Mesopotamia’s Intermediate Period: 2000–1600 BC

Tensions between local headmen and the palace

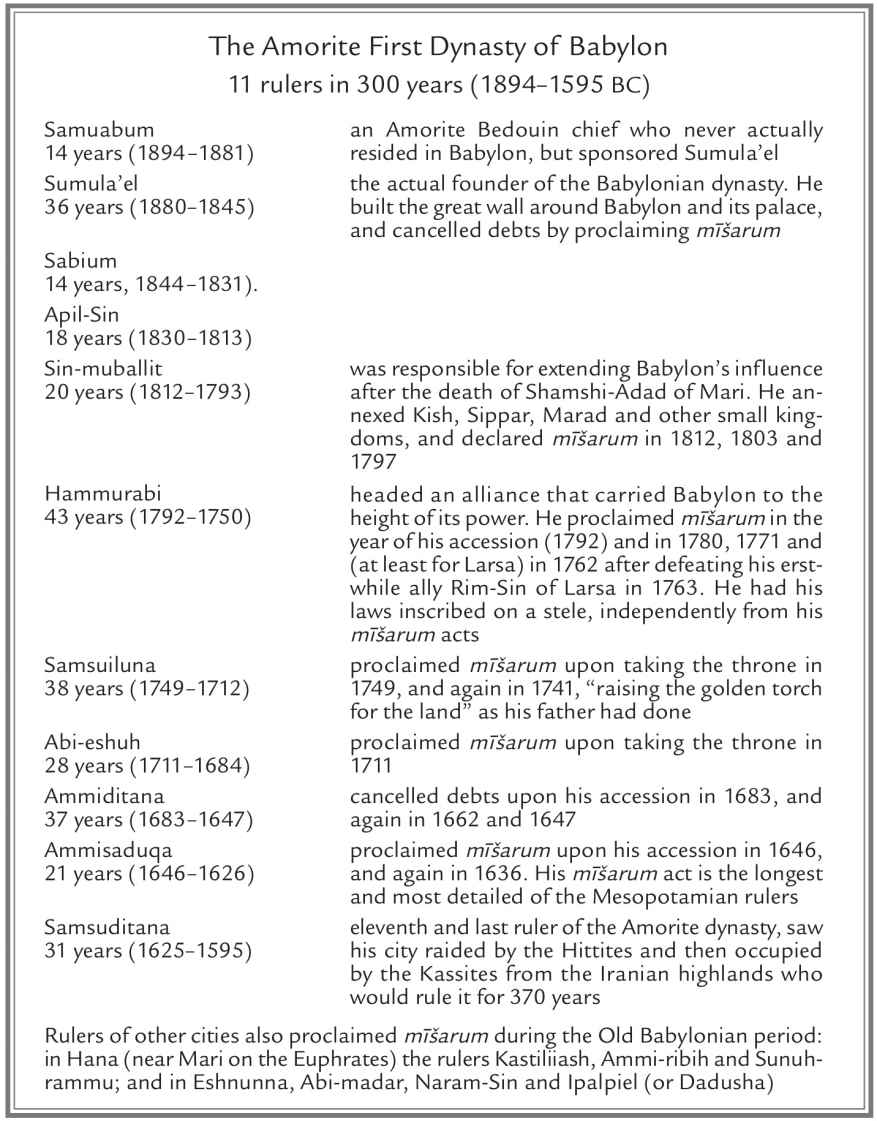

16. Hammurabi’s Laws and mı-šarum Edicts: 1792–1750 BC

Retaining the loyalty of Babylonia’s cultivators by proclaiming mı-šarum

Growing palace power over the temples and landed communities

17. Freeing the Land and its Cultivators from Predatory Creditors

Laws saving citizens from debt bondage

Hammurabi’s philosophy of deterrence regarding creditor abuses

18. Samsuiluna’s and Ammisaduqa’s mı-šarum Edicts: 1749 and 1646 BC

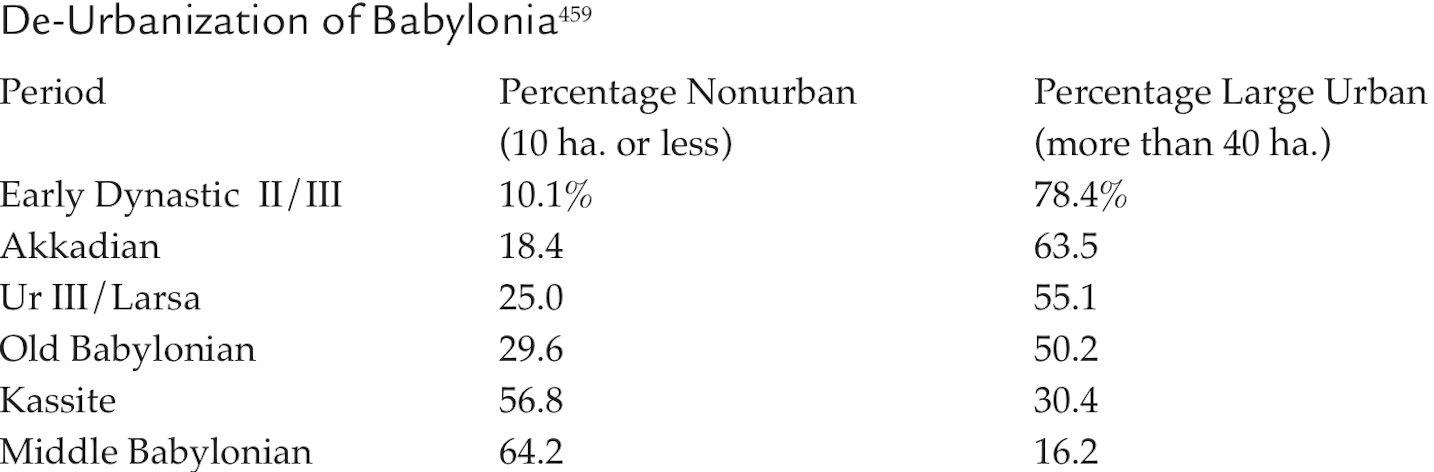

19. Social Cosmology of Babylonia’s Debt Cancellations

Military conflict and land pressure make mīšarum proclamations more frequent

20. Usury and Privatization in the Periphery, 1600–1200 BC

The Hurrian-Hittite “Song of Release” extends the application of andurārum

21. From the Dawn of the Iron Age to the Rosetta Stone

Debt amnesties in the Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian empires

The Inscriptions of Sargon II (722 to 705) and his grandson Esarhaddon (681 to 669)

22. Judges, Kings and Usury: 8th and 7th Centuries BC

23. Biblical Laws Call for Periodic Debt Cancellation

The Priestly Code of Deuteronomy

Jeremiah depicts the Babylonian captivity as divine retaliation for violating the Covenant

24. The Babylonian Impact on Judaic Debt Laws

Ezekiel’s apocalyptic message in the face of Judah’s defeat by Babylonia

Recasting Babylonian andurārum proclamations in a Yahwist context

25. From Religious Covenant to Hillel

How Hillel’s prosbul yielded power to creditors and land appropriators

26. Christianity Spiritualizes the Jubilee Year as the Day of Judgment

The Novels of Basil and Romanus protecting smallholders from the dynatoi

Romanos’ Novel of 934 barring dynatoi from acquiring village land

28. Zenith and Decline of Byzantium: 945–1204

29. Western Civilization is Rooted in the Bronze Age Near East

How creditor appropriation turned land into “private property”

Bronze Age money as a means of palatial production and trade accounting

The inherent inability of personal and agrarian debts to be paid over the long run

Acknowledgements

For over thirty years I have discussed the ideas in this book with Carl Lamberg-Karlovsky at Harvard’s Peabody Museum. Together, we organized the series of five ISLET-ISCANEE colloquia that form the basis for the economic history of the Bronze Age Near East that forms the core of this book. Cornelia Wunsch has constantly drawn my attention to the relevant literature and helped me avoid anachronistic interpretations. She has played the major editorial role as publisher of this book and the ISLET colloquia.

Steven Garfinkle has focused my attention on the role of entrepreneurial trade and credit in its symbiosis with the palatial economy. Marc Van De Mieroop has given steady advice and perspective over the decades, and Baruch Levine was an early guide and co-editor regarding Judaic economic history. All these readers have been helpful in alerting me to the relevant bibliography.

David Graeber has been helpful in emphasizing the anthropological setting for how debt has evolved and the diverse ways of treating debtors who are unable to pay. Charles Goodhart has helped emphasize the relevance of the history of debt jubilees to today’s financial crisis. Dirk Bezemer also has co-written articles with me drawing this linkage and applying it to modern economic theory and statistics.

Lynn Yost has provided editorial help with early drafts of this book, and Ashley Dayman has proofread the manuscript and found many improvements.

My web manager, Karl Fitzgerald, has hosted ongoing radio discussions on my interpretation of ancient Near Eastern history. Early versions of some of this work also have appeared on Naked Capitalism and Counterpunch.

Throughout the decades it has taken me to complete this book, my wife Grace has been a constant supporter and provided many types of help. I could not have completed it without her love and encouragement.

The Rise and Fall of Jubilee Debt Cancellations and Clean Slates

The idea of annulling debts nowadays seems so unthinkable that most economists and many theologians doubt whether the Jubilee Year could have been applied in practice, and indeed on a regular basis. A widespread impression is that the Mosaic debt jubilee was a utopian ideal. However, Assyriologists have traced it to a long tradition of Near Eastern proclamations. That tradition is documented as soon as written inscriptions have been found – in Sumer, starting in the mid-third millennium BC.

Instead of causing economic crises, these debt jubilees preserved stability in nearly all Near Eastern societies. Economic polarization, bondage and collapse occurred when such clean slates stopped being proclaimed.

What were Debt Jubilees?

Debt jubilees occurred on a regular basis in the ancient Near East from 2500 BC in Sumer to 1600 BC in Babylonia and its neighbors, and then in Assyria in the first millennium BC. It was normal for new rulers to proclaim these edicts upon taking the throne, in the aftermath of war, or upon the building or renovating a temple. Judaism took the practice out of the hands of kings and placed it at the center of Mosaic Law.i

By Babylonian times these debt amnesties contained the three elements that Judaism later adopted in its Jubilee Year of Leviticus 25. The first element was to cancel agrarian debts owed by the citizenry at large. Mercantile debts among businessmen were left in place.

A second element of these debt amnesties was to liberate bondservants – the debtor’s wife, daughters or sons who had been pledged to creditors. They were allowed to return freely to the debtor’s home. Slave girls that had been pledged for debt also were returned to the debtors’ households. Royal debt jubilees thus freed society from debt bondage, but did not liberate chattel slaves.

A third element of these debt jubilees (subsequently adopted into Mosaic law) was to return the land or crop rights that debtors had pledged to creditors. This enabled families to resume their self-support on the land and pay taxes, serve in the military, and provide corvée labor on public works.

Commercial “silver” debts among traders and other entrepreneurs were not subject to these debt jubilees. Rulers recognized that productive business loans provide resources for the borrower to pay back with interest, in contrast to consumer debt. This was the contrast that medieval Schoolmen later would draw between interest and usury.

Most non-business debts were owed to the palace or its temples for taxes, rents and fees, along with beer to the public ale houses. Rulers initially were cancelling debts owed mainly to themselves and their officials. This was not a utopian act, but was quite practical from the vantage point of restoring economic and military stability. Recognizing that a backlog of debts had accrued that could not be paid out of current production, rulers gave priority to preserving an economy in which citizens could provide for their basic needs on their own land while paying taxes, performing their corvée labor duties and serving in the army.

Most personal debts were not the result of actual loans, but were accruals of unpaid agrarian fees, taxes and kindred obligations to royal collectors or temple officials. Rulers were aware that these debts tended to build up beyond the system’s ability to pay. That is why they cancelled “barley” debts in times of crop failure, and typically in the aftermath of war. Even in the normal course of economic life, social balance required writing off debt arrears to the palace, temples or other creditors so as to maintain a free population of families able to provide for their own basic needs.

As interest-bearing credit became privatized throughout the Near Eastern economies, personal debts owed to local headmen, merchants and creditors also were cancelled. Failure to write down agrarian debts would have enabled officials and, in due course, private creditors, merchants or local headmen to keep debtors in bondage and their land’s crop surplus for themselves. Crops paid to creditors were not available to be paid to the palace or other civic authorities as taxes, while labor obliged to work off debts to creditors was not available to provide corvée service or serve in the army. Creditor claims thus set the wealthiest and most ambitious families on a collision course with the palace, along the lines that later occurred in classical Greece and Rome. In addition to preserving economic solvency for the population, rulers thus found debt cancellation to be a way to prevent a financial oligarchy from emerging to rival the policy aims of kings.

Cancelling debts owed to wealthy local headmen limited their ability to amass power for themselves. Private creditors therefore sought to evade these debt jubilees. But surviving legal records show that royal proclamations were, indeed, enforced. Through Hammurabi’s dynasty these “andurārum acts” became increasingly detailed so as to close loopholes and prevent ploys that creditors tried to use to gain control of labor, land and its crop surplus.

Social purpose of Debt Jubilees

The common policy denominator spanning Bronze Age Mesopotamia and the Byzantine Empire in the 9th and 10th centuries was the conflict between rulers acting to restore land to smallholders so as to maintain royal tax revenue and a land-tenured military force, and powerful families seeking to deny its usufruct to the palace. Rulers sought to check the economic power of wealthy creditors, military leaders or local administrators from concentrating land in their own hands and taking the crop surplus for themselves at the expense of the tax collector.

By clearing the slate of personal agrarian debts that had built up during the crop year, these royal proclamations preserved a land-tenured citizenry free from bondage. The effect was to restore balance and sustain economic growth by preventing widespread insolvency.

Babylonian scribes were taught the basic mathematical principle of compound interest, whereby the volume of debt increases exponentially, much faster than the rural economy’s ability to pay.ii That is the basic dynamic of debt: to accrue and intrude increasingly into the economy, absorbing the surplus and transferring land and even the personal liberty of debtors to creditors.

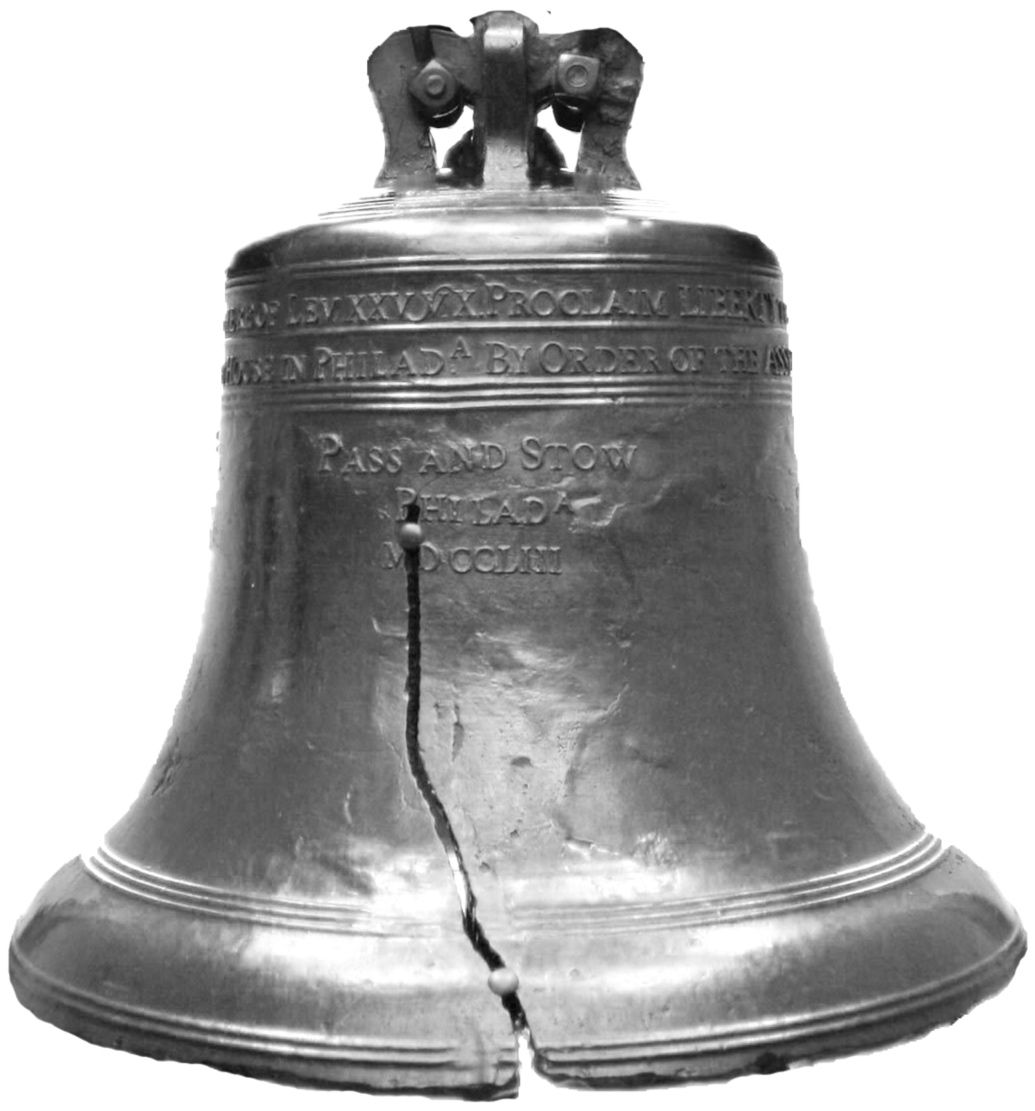

Debt jubilees were designed to make such losses of liberty only temporary. The Mosaic injunction (Leviticus 25), “Proclaim liberty throughout the land,” is inscribed on America’s Liberty Bell. That is a translation of Hebrew deror, the debt Jubilee, cognate to Akkadian andurārum. The liberty in question originally was from debt peonage.

To insist that all debts must be paid, regardless of whether this may bankrupt debtors and strip away their land and means of livelihood, stands at odds with the many centuries of Near Eastern clean slates. Their success stands at odds with the assumption that creditor interests should take priority over those of the indebted economy at large.

In sum, the economic aim of debt jubilees was to restore solvency to the population as a whole. Many royal proclamations also freed businesses from various taxes and tariff duties, but the main objective was political and ideological. It was to create a fair and equitable society.

This ethic was not egalitarian as such. It merely aimed to provide citizens with the basic minimum standard needed to be self-sustaining. Wealth accumulation was permitted and even applauded, as long as it did not disrupt the normal functioning of society at large.

How well did Debt Jubilees succeed?

Creditors sought to avoid these laws, but Babylonian legal records show that the debt cancellations of Hammurabi’s dynasty and those of his neighbors were enforced. These proclamations enabled society to avert military defeat by preserving a land-tenured citizenry as the source of military fighters, corvée labor and the tax base. The Bronze Age Near East thus avoided the economic polarization between creditors and debtors that ended up imposing bondage on most of classical antiquity.

In the 7th-century BC, Greek populist leaders called tyrants (at that time with no original pejorative meaning) paved the way for the economic takeoff of Sparta, Corinth and Aegina by cancelling debts and redistributing the lands monopolized by their cities’ aristocracies. In Athens, Solon’s banning of debt bondage and clearing the land of debts in 594 BC avoided the land redistributions to the rich and powerful that much of the population had feared.

So popular was the demand for a debt jubilee that the 4th-century BC Greek general Aeneas Tacticus advised attackers of cities to draw the population over to their side by cancelling debts, and for defenders to hold onto the loyalty of their population by making the same offer. Cities that refrained from cancelling debts were conquered, or fell into widespread bondage, slavery and serfdom.

That ultimately is what happened in Rome. Its historians describe how disenfranchising indebted citizens led to the hiring of mercenaries (often debtors expropriated from their family homestead) as wealthy creditors concentrated land in their own hands, along with law-making power and control of state religion. What, instead, threatened the security of widely-held property and ultimately led to collapse was the financial oligarchy’s ending of the power of rulers to restore liberty from bondage and to save debtors from being deprived of land tenure on a widespread scale.

Plutarch’s lives of Sparta’s kings Agis and Cleomenes shows a problem of cancelling mortgage debts other than those owed by owner-occupants. A land speculator had bought property on credit, and hoped to have his debts annulled along with those of smallholders who were supposed to be the nominal beneficiaries. One can well imagine cancelling today’s mortgage debts of investors who have bought their real estate on credit, with the loan to be paid out of the rent. Instead of the bankers or the tax collector receiving the rental value, the landlords would be by far the greatest windfall gainers. Plutarch’s narrative shows that if all property debts were cancelled, it would be necessary to adjust the tax system to collect the appropriate rental value of such properties in the tax base, in order to prevent a windfall gain. Otherwise, absentee owners would gain instead of the actual occupants and users of the economy’s debt-financed real estate.

Why did debt Jubilees fall into disuse?

Throughout history a constant political dynamic has been maneuvering by creditors to overthrow royal power capable of enforcing debt amnesties and reversing foreclosures on homes and subsistence land. The creditors’ objective is to replace the customary right of citizens to self-support by its opposite principle: the right of creditors to foreclose on the property and means of livelihood pledged as collateral (or to buy it at distress prices), and to make these transfers irreversible. The smallholders’ security of property is replaced by the sanctity of debt instead of its periodic cancellation.

Archaic restorations of order ended when the forfeiture or forced sale of self-support land no longer could be reversed. When creditors and absentee landlords gained the upper political hand, reducing the economic status for much of the population to one of debt dependency and serfdom, classical antiquity’s oligarchies used their economic gains, military power or bureaucratic position to buy up the land of smallholders, as well as public land such as Rome’s ager publicus.iii

Violence played a major political role, almost entirely by creditors. Having overthrown kings and populist tyrants, oligarchies accused advocates of debtor interests of being “tyrants” (in Greece) or seeking kingship (as the Gracchi brothers and Julius Caesar were accused of in Rome). Sparta’s kings Agis and Cleomenes were killed for trying to cancel debts and reversing the monopolization of land in the 3rd century BC. Neighboring oligarchies called on Rome to overthrow Sparta’s reformer-kings.iv

The creditor-sponsored counter-revolution against democracy led to economic polarization, fiscal crisis, and ultimately to being conquered – first the Western Roman Empire and then Byzantium. Livy, Plutarch and other Roman historians blamed Rome’s decline on creditors using fraud, force and political assassination to impoverish and disenfranchise the population. Barbarians had always stood at the gates, but only as societies weakened internally were their invasions successful.

Today’s mainstream political and economic theories deny a positive role for government policy to constrain the large-scale concentration of wealth. Attempting to explain the history of inequality since the Stone Age, for instance, Stanford historian Walter Scheidel’s 2017 book The Great Leveler downplays the ability of State policy to reduce such inequality substantially without natural disasters wiping out wealth at the top. He recognizes that the inherent tendency of history is for the wealthy to win out and make society increasingly unequal. This argument also has been made by Thomas Piketty and based largely on the inheritance of great fortunes (the same argument made by his countryman Saint-Simon two centuries earlier). But the only “solutions” to inequality that Scheidel finds at work are the four “great levelers”: warfare, violent revolution, lethal pandemics or state collapse. He does not acknowledge progressive tax policy, limitations on inherited wealth, debt writeoffs or a replacement of debt with equity as means of preventing or reversing the concentration of wealth in the absence of an external crisis.

The Book of Revelation forecast these four plagues as punishment for the greed and inequity into which the Roman Empire was falling. By Late Roman times there seemed no alternative to the Dark Age that was descending. Recovery of a more equitable past seemed politically hopeless, and so was idealized as occurring only by divine intervention at the end of history. Yet for thousands of years, economic polarization was reversed by cancelling debts and restoring land tenure to smallholders who cultivated the land, fought in the army, paid taxes and/or performed corvée labor duties. That also would be Byzantine policy to avoid polarization from the 7th through 10th centuries, echoing Babylonia’s royal proclamation of clean slates.

Within Judaism, rabbinical orthodoxy attributed to Hillel developed the prosbul clause by which debtors waived their right to have their debts cancelled in the Jubilee Year. Hillel claimed that if the Jubilee Year were maintained, creditors would not lend to needy debtors – as if most debts were the result of loans, not arrears to Roman tax collectors and other unpaid bills. Opposing this pro-creditor argument, Jesus announced in his inaugural sermon that he had come to proclaim the Jubilee Year of the Lord cited by Isaiah, whose scroll he unrolled. His congregation is reported to have reacted with fury. (Luke 4 tells the story). Like other populist leaders of his day, Jesus was accused of seeking kingship to enforce his program on creditors.

Subsequent Christianity gave the ideal of a debt amnesty an otherworldly eschatological meaning as debt cancellation became politically impossible under the Roman Empire’s military enforcement of creditor privileges. Falling into debt subjected Greeks and Romans to bondage without much hope of recovering their liberty. They no longer could look forward to the prospect of debt amnesties such as had annulled personal debts in Sumer, Babylonia and their neighboring realms, liberating citizens who had fallen into bondage or pledged and lost their land tenure rights to foreclosing creditors.

The result was destructive. The only debts that Emperor Hadrian annulled were Rome’s tax records, which he burned in 119 AD – tax debts owed to the palace, not debts to the creditor oligarchy that had gained control of Rome’s land.

A rising proportion of Greeks and Romans lost their liberty irreversibly. The great political cry throughout antiquity was for debt cancellation and land redistribution. But it was achieved in such classical times only rarely, as when Greece’s 7th-century BC tyrants overthrew their cities’ aristocracies who had monopolized the land and were subjecting the citizenry to debt dependency. The word “tyrant” later became a term of invective, as if liberating Greek populations from bondage to a narrow hereditary ethnic aristocracy was not a precondition for establishing democracy and economic freedom.

A study of the long sweep of history reveals a universal principle to be at work: The burden of debt tends to expand in an agrarian society to the point where it exceeds the ability of debtors to pay. That has been the major cause of economic polarization from antiquity to modern times. The basic principle that should guide economic policy is recognition that debts which can’t be paid, won’t be. The great political question is, how won’t they be paid?

There are two ways not to pay debts. Our economic mainstream still believes that all debts must be paid, leaving them on the books to continue accruing interest and fees – and to let creditors foreclose when they do not receive the scheduled interest and amortization payment.

This is what the U.S. President Obama did after the 2008 crisis. Homeowners, credit-card customers and other debtors had to start paying down the debts they had run up. About 10 million families lost their homes to foreclosure. Leaving the debt overhead in place meant stifling and polarizing the economy by transferring property from debtors to creditors.

Today’s legal system is based on the Roman Empire’s legal philosophy upholding the sanctity of debt, not its cancellation. Instead of protecting debtors from losing their property and status, the main concern is with saving creditors from loss, as if this is a prerequisite for economic stability and growth. Moral blame is placed on debtors, as if their arrears are a personal choice rather than stemming from economic strains that compel them to run into debt simply to survive.

Something has to give when debts cannot be paid on a widespread basis. The volume of debt tends to increase exponentially, to the point where it causes a crisis. If debts are not written down, they will expand and become a lever for creditors to pry away land and income from the indebted economy at large. That is why debt cancellations to save rural economies from insolvency were deemed sacred from Sumer and Babylonia through the Bible.

See ENDNOTES: Rise and Fall of Jublilee Debt Cancellations and Clean Slates

Archaic Economies versus Modern Preconceptions

Our epoch is strangely selective when it comes to distinguishing between what is plausibly historical and believable in the Bible, and what seems merely mythic or utopian. Fundamentalist Christians show their faith that God created the earth in six days (on Sunday, October 23, 4004 BC according to Archbishop James Ussher in 1650) by building museums with dioramas showing humans cavorting alongside dinosaurs. While deeming this literal reading of Genesis to be historical, they ignore the Biblical narrative describing the centuries-long struggle between debtors and creditors. The economic laws of Moses and the Prophets, which Jesus announced his intention to revive and fulfill, are brushed aside as anachronistic artifacts, not the moral center of the Old and New Testaments, the Jewish and Christian bibles. The Jubilee Year (Leviticus 25) is the “good news” that Jesus – in his first reported sermon (Luke 4) – announced that he had come to proclaim.

Today the idea of annulling debts seems so unthinkable that not only economists but also many theologians doubt whether the Jubilee Year could have been applied regularly in practice. The widespread impression is that this Mosaic Law was a product of utopian idealism. But Assyriologists have traced it to a long tradition of royal debt cancellations from Sumer in the third millennium BC and Babylonia (2000–1600 BC) down through first-millennium Assyria. This book summarizes this long Near Eastern tradition and how it provided the model for the Jubilee Year.

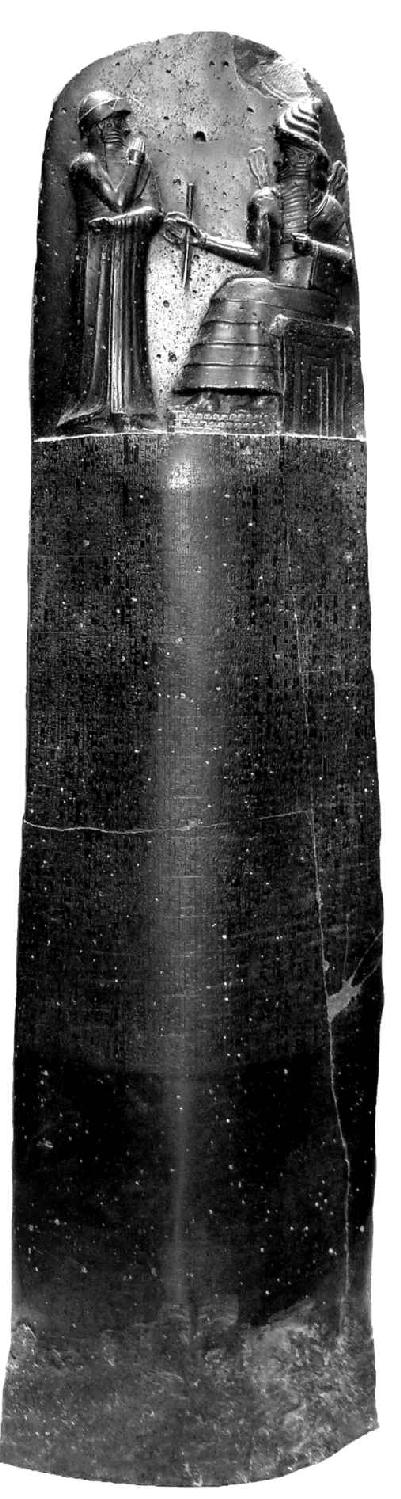

Hammurabi’s Babylonian laws became instantly famous when they were discovered in 1901 and translated the next year. Less familiar is the fact that nearly each member of his dynasty inaugurated his rule by proclaiming a debt amnesty – andurārum, the source of Hebrew cognate deror, the Jubilee Year, which has the same root as its Babylonian model. Personal agrarian debts were cancelled, although commercial “silver” debts were left intact. Bondservants pledged to creditors were returned to the debtor’s family. And land or crop rights pledged to creditors or sold under distress conditions were returned to their customary holders.

These rules are so far at odds with the creditor-oriented ideology of our times that the instinctive response is to deny that they could have worked. For starters, why would creditors be willing lend if they thought that a debt annulment or Jubilee Year was coming? Wouldn’t the economy be disrupted when credit dried up?

This criticism is anachronistic, because most agrarian debts did not stem from actual loans. They mounted up as unpaid bills, starting with fees and taxes owed to the palace. Early economies operated on credit, not cash on the barrelhead. Much like modern drinkers running up a bar tab, Babylonians ran up debts to alewives. Their bills were put on the tab, to be paid on the threshing floor at harvest time.[1] It was out of these crop payments that pub keepers (literally public agents) paid what they owed to the palace or temple for their consignments of beer. Other personal debts were owed out of the harvest to palace collectors for irrigation water, seeds and other inputs needed during the time gap from planting to harvesting. Palaces and temples or their officials were the main early creditors, advancing agricultural inputs and various consumer goods.[2]

When harvests failed as a result of drought, flood or pests, there was not enough crop surplus to pay agrarian debts. In such cases rulers cancelled debts owed above all to themselves and their officials, and increasingly to private creditors as well. The palace had little interest in seeing these creditors force debtors into bondage. Rulers needed a free population to field an army and provide corvée labor to build city walls and temples and dig irrigation ditches.

This principle of keeping debts in line with the ability to pay and forgiving them under extenuating circumstances also governed commercial shipping loans. From Hammurabi’s laws down to those of Rome, such mercantile debts were annulled in cases of shipwreck or piracy, and for overland caravans that were robbed.

Another modern objection to the practicality of debt cancellations concerns property rights. If land is periodically returned to its customary family holders, how can it be bought and sold? The answer is that self-support land (unlike townhouses) was not supposed to be sold as a market commodity. Security of land tenure was part of the quid pro quo obliging holders to serve in the military and perform corvée labor.[3] If wealthy creditors were permitted to “join house to house and lay field to field ... until there is no more room and you alone are left in the land” (Isaiah 5.8) while reducing debtors to bondage, who would be left to build infrastructure and fight to defend against the ever-present aggressors?

These public needs took priority over the acquisitive ambitions of creditors. Cancelling debts did not disrupt economic activity, nor did it violate the idea of good economic order. By saving debtors from falling into servitude to a financial oligarchy, such amnesties preserved the liberty of citizens and their subsistence land rights. These acts were a precondition for maintaining economic stability. Indeed, proclaiming amnesty to restore the body politic – like periodically returning exiles from cities of refuge – was common to Native American as well as Biblical practice. The logic seems universal.

It was customary for Near Eastern rulers to proclaim amar–gi or mīšarum upon taking the throne for their first full year, and also on the occasions when droughts or floods prevented crop debts from being paid. Cancelling debts and restoring land rights reasserted royal authority over creditors engaging in usury to obtain the labor of debtors at the expense of the palace. The practice goes back to Sumerian amar–gi attested by Lagash’s ruler Enmetena c. 2400 BC. Down to nearly 1600 BC in Babylonia, the texts of Clean Slate mīšarum proclamations grew increasingly detailed to prevent creditors from developing loopholes. Cancellations of payment arrears and other debts to the palace, temples and their collectors or local creditors are found throughout the ancient Near East, in the Assyrian trade colonies in what is now Turkey, to first-millennium Assyria and the Jewish lands.

As credit became more widely privatized, usury became the major lever to pry away land and crop rights, and to reduce labor to irreversible bondage. The process culminated with classical antiquity’s oligarchies replacing “divine kingship” with creditor-oriented rules. To resist widespread bondage and expropriation of debtors, Judaism placed debt cancellation at the core of Mosaic Law.

✽✽✽

My own professional training is as an economist. During the 1960s and 1970s I wrote articles and books warning that Third World debts could not be paid – or those of the United States for that matter.[4] I came to this conclusion working as Chase Manhattan’s balance-of-payments analyst in the mid-1960s. It was apparent that the U.S. and other governments could pay their debts only by borrowing from foreign creditors – adding the interest charges onto the debt, so that the amount owed grew at an exponential rate. This was “the magic of compound interest.” Over time it makes any economy’s overall volume of debts unpayably high.

In the late 1970s I wrote a series of papers for the United Nations Institute for Training and Development (UNITAR) warning that Third World economies could not pay their foreign debts and that a break was imminent. It came in 1982 when Mexico announced it could not pay, triggering the Latin American “debt bomb,” leading to the Brady Plan to write down debts. The capstone of the UNITAR project was a 1980 meeting in Mexico hosted by its former president, Luis Echeverria, who had helped draft the text for the New International Economic Order (NIEO).[5] An angry fight broke out over my insistence that Latin American debtors would soon have to default.

The pro-creditor U.S. rapporteur for the meeting gave a travesty of my position in his summation. When I stood up and announced that I was pulling out my colleagues in response to this censorship, I was followed out of the hall by Russian and Third World delegates. In the aftermath, Italian banks financially backing the UNITAR project said that they would withdraw funding if there was any suggestion that sovereign debts could not be paid. The idea was deemed unthinkable – or so creditor lobbyists wanted the world to believe. But most banks knew quite well that global lending would end in default.

This experience drove home to me how controversial the idea of debt writedowns was. I set about compiling a history of how societies through the ages had felt obliged to write down their debts, and the political tensions this involved.

It took me about a year to sketch the history of debt back to classical Greece and Rome. Livy, Diodorus and Plutarch described how Roman creditors waged a century-long Social War (133–29 BC) turning democracy into oligarchy. But among modern historians, Arnold Toynbee is almost alone in emphasizing the role of debt in concentrating Roman wealth and property ownership.

By the time Roman creditors won, the Pharisee Rabbi Hillel had innovated the prosbul clause in debt contracts, whereby debtors waived their right to have their debts annulled in the Jubilee Year. This is the kind of stratagem that today’s banks use in the “small print” of their contracts obliging users to waive their rights to the courts and instead submit to arbitration by bank-friendly referees in case of dispute over credit cards, bank loans or general bank malfeasance. Creditors had tried to use similar clauses already in the Old Babylonian era, but these were deemed illegal under more pro-debtor royal law.

In researching the historical background of the Jubilee Year, I found occasional references to debt cancellations going back to Sumer in the third millennium BC. The material was widely scattered through the literature, because no history of Near Eastern economic institutions and enterprise had been written.[6] Most history depicts our civilization as starting in Greece and Rome, not in the preceding thousands of years when the techniques of commercial enterprise, finance and accounting were developed. So I began to search through the journal literature and relatively few books on Sumer and Babylonia. “Debt” rarely appeared in the indexes. It was buried in the discussion of other topics.[7]

Not being able to read cuneiform, I was obliged to rely on translations – and was struck by how radically the versions in each language differed when it came to the terms used for royal proclamations. The American Noah Kramer translated the Sumerian amar–gi in texts of the third-millennium Lagash ruler Urukagina as a “tax reduction.” In 1980 he even urged incoming President Ronald Reagan to emulate this policy, as if Urukagina were a proto-Republican.[8] The British Assyriologist Wilfred Lambert explained to me that andurārum meant “free trade” – typical of English policy since it abolished its Corn Laws in 1846. Looking at the Assyrian trade, Mogens Larsen of Denmark agreed with this reading.[9] The German Fritz Kraus saw the royal edicts of Hammurabi’s dynasty as what they certainly were: debt cancellations. But I found the most enlightening reading to be that of the French Assyriologist Dominique Charpin: “restoration of order.”

All these translators knew that the basic root of Sumerian amar–gi is “mother” (ama), as in “mother condition.” This was an idealized original state of economic balance with no personal or agrarian debt arrears or debt bondage (but with slavery for captured prisoners and others, to be sure).[10]

Even before reading Charpin’s books and articles, it was obvious that what was needed to understand the meaning of royal inscriptions was more than just linguistics. It was necessary to reconstruct the overall worldview and indeed, social cosmology at work. In 1984, after three years of research, I showed my findings to my friend Alex Marshack, an Ice Age archaeologist associated with Harvard’s Peabody Museum, the university’s anthropology department. He passed on my summary to its director, Carl Lamberg-Karlovsky, who invited me up for a weekend to discuss it. The upshot was an invitation to become a Research Fellow at Peabody in Babylonian economic archaeology. For the next decade we discussed the Bronze Age economy and structures out of which interest-bearing debt is first documented.

I presented my first academic paper on the ancient Near East in 1990, tracing how interest was developed in Mesopotamia, most likely initially to finance foreign trade, and how Syrian and Levantine traders brought the practice to the Mediterranean lands only around the 8th century BC.[11] In Greece and Rome, however, charging interest was not accompanied by debt cancellations. Charging interest was brought from the Near East and transplanted in a new context of chieftains and clan leaders who used interest-bearing usury to reduce populations to a state of dependency, creating oligarchies that soon were overthrown from Sparta to Corinth, until Solon’s debt reforms in Athens in 594 BC. Classical antiquity’s “takeoff” thus adopted Near Eastern economic practices in an increasingly oligarchic context. Tension between creditors and debtors led to ongoing political and economic turmoil.

Widespread misinterpretation of Neolithic and Bronze Age society

My long view meant that interest-bearing debt did not evolve “anthropologically” out of tribal practices of the early Greeks, Romans or other Europeans, as was claimed by Mauss in The Gift (1925). The Near Eastern Bronze Age was the formative era of Western civilization’s economic institutions. But there is still a tendency to isolate Near Eastern development from that of classical antiquity.

Market-oriented financial historians have woven origin myths about allegedly primitive individuals lending cows in return for some of their calves as a bonus, or loans of new tools for a share of the added output they produce. These anachronistic fables depict our Stone Age ancestors as following modern individualistic logic. Thorstein Veblen poked fun already a century ago at such descriptions based on a “simple scheme of economic life … to throw into the foreground, in a highly unreal perspective, those features which lend themselves to interpretation in terms of the normalised competitive system.”[12] According to such presumptions, the temples and palaces of Sumer and Babylonia (and by extension, modern public institutions) could not play a productive role, but were only a burdensome overhead.

Such armchair preconceptions are based on how modern castaways on a desert island would organize life. If these individuals found themselves stranded back in the Bronze Age, they probably would have done to Mesopotamia what neoliberals have done to post-Soviet countries and the Eurozone. Privatizers, bankers and other grandees would lord it over a dependent labor force, leading to emigration such as the past decade has seen from Latvia, Ukraine and Greece (about 20 percent of working-age adults in each case). It was to avoid such flight that ancient rulers sought to maintain their populations intact with basic means of self-support, free from creditor claims and willing to fight for their communities and to provide corvée labor to build up their infrastructure.

These early societies were not egalitarian. Wealth was concentrated at the top of the social pyramid, largely via temples and palaces acting ostensibly on behalf of the citizenry. But the more one looks at archaic societies, the clearer it becomes that there is no single “natural” way to organize them. That perception has led Assyriologists and Near Eastern archaeologists to avoid much interaction with the economics discipline, both the individualistic school and “temple state” or Oriental Despotism ideologues. And economists for their part likewise shy away from discussing the ancient Near East, because its institutions are so at odds with modern theories and assumptions about how economies are supposed to work.

To explain how debt originated – and what kinds of debts were cancelled regularly – it is necessary to discuss the social and anthropological context in which debt and credit, money and interest were innovated. The Bronze Age Near East was organized on principles so different from those of today that it seems unconnected to modern civilization. That is why most economists and social theorists prefer to pick up the historical thread with the more familiar Greece and Rome. There is a problem of cognitive dissonance and outright ideological rejection in dealing with the ancient Near East, precisely because its organizing principles and economic dynamics are so far at odds with those of today’s mainstream economics and popular opinion. Most mainstream social science misses the point that the temples and palaces of the ancient Near East were the initial innovators of commercial enterprise and accounting, money and interest, standardized prices, weights and measures. As for anthropologists, their focus is more on tribal enclaves that have not developed into full-blown civilization.

The International Scholars Conference on Ancient Near Eastern Economies (ISCANEE)

By 1993, I had written a draft of the present book, but it was not a propitious time to talk of debt cancellation. The financial bubble was just taking off, and seemed to promise a way for most people to get rich. One reader for a university press found it unthinkable that debts could have been annulled on a widespread level, and intimated that the Assyriological profession had always believed this.

That was almost the case in the 1980s. The most popular books on Sumer for the general audience were written by a politically conservative literary specialist, Samuel Kramer, who believed that if debts were indeed cancelled, it would only have been temporarily during a royal festival. Today’s Assyriological mainstream have come to accept the idea that debts were annulled and financial clean slates proclaimed with more lasting effect again and again.

Part of this turnaround was catalyzed by a series of colloquia that I organized with the Peabody Museum to reconstruct the origins of modern economic practices, enterprise and finance. Our group brought together leading Assyriologists, Egyptologists and other specialists to describe the early evolution of debt, land tenure and the privatization of enterprise in their specific areas and time periods of expertise.

At the outset we envisioned three colloquia. Our first area of study, in 1994, was the structure of “mixed” economies and how the temples and palaces – the largest economic institutions of their day – assigned or leased trade and other enterprise to private merchants and operators and lead to the publication of Privatization in the Ancient Near East and Classical Antiquity.[13] Land was the most important asset to be privatized, and debt was the major lever prying land away from communal tenure. So our second colloquium, in 1996 at New York University, was on land tenure and the origins of urbanization and fiscal authority, published as Urbanization in the Ancient Near East.[14] By this time our group had gained some renown and we held a supplementary 1997 meeting on this same topic in Saint Petersburg at Russia’s Oriental Institute, with attendees including scholars relatively unknown in the West.

The specialists that we assembled during what became five colloquia on the economic history of the ancient Near East will be cited often in the chapters that follow. Archaeologists included Karl Lamberg-Karlovsky, his Harvard Peabody Museum colleague Alex Marshack traced urban iconography back to seasonal Ice Age gathering points, and Giorgio Buccellati, the excavator of Urkesh in northern Syria. The Sumerologists included Dietz O. Edzard of Munich University and, also from Germany, Johannes Renger, a leading follower of Karl Polanyi. The Neo-Babylonian specialists were Michael Jursa of the University of Vienna and Cornelia Wunsch of SOAS and Berlin. From Russia’s Institute of Oriental Studies in Saint Petersburg, our group had Muhammed Dandamayev and Nelli Kozyreva. From England were Eleanor Robson from Oxford and Karen Radner from the University of London. And from the United States were Marc Van De Mieroop of Columbia University, Piotr Steinkeller of Harvard, Seth Richardson from the University of Chicago, Elizabeth Stone from SUNY Stony Brook, William Hallo of Yale, and Robert Englund from UCLA. For northern Mesopotamia our group included Alfonso Archi to deal with Ebla, and for upstream Nuzi, Carlo Zaccagnini from Naples and Maynard Maidman from the University of Toronto. For Bronze Age Mycenaean Greece we had Tom Palaima from the University of Texas and his colleague Dimitri Nakassis. Our group’s Egyptologists were headed by Ogden Goelet of New York University, the archaeologist Mark Lehner of Harvard and Edward Bleiberg of the Brooklyn Museum of Art. From ancient Israel, Baruch Levine, and Michael Heltzer for the Syrian coast city of Ugarit.

Having established the role of debt in foreclosing on land rights and obtaining labor to work off personal debts, our third colloquium dealt with credit and Clean Slate proclamations. Held in 2000 at Columbia University, that conference provided the basic narrative of the present book, tracing the origin of commercial and personal agrarian debt, and the continuity of Clean Slates. Only personal agrarian barley debts were annulled, not commercial silver debts among merchants. And only subsistence landholdings were returned to their customary holders, not townhouses and other wealth over and above the basic subsistence needs of citizens. So the aim was not equality as such, but the assurance of self-support land and production for the citizenry. The pertaining volume is Debt and Economic Renewal in the Ancient Near East.[15]

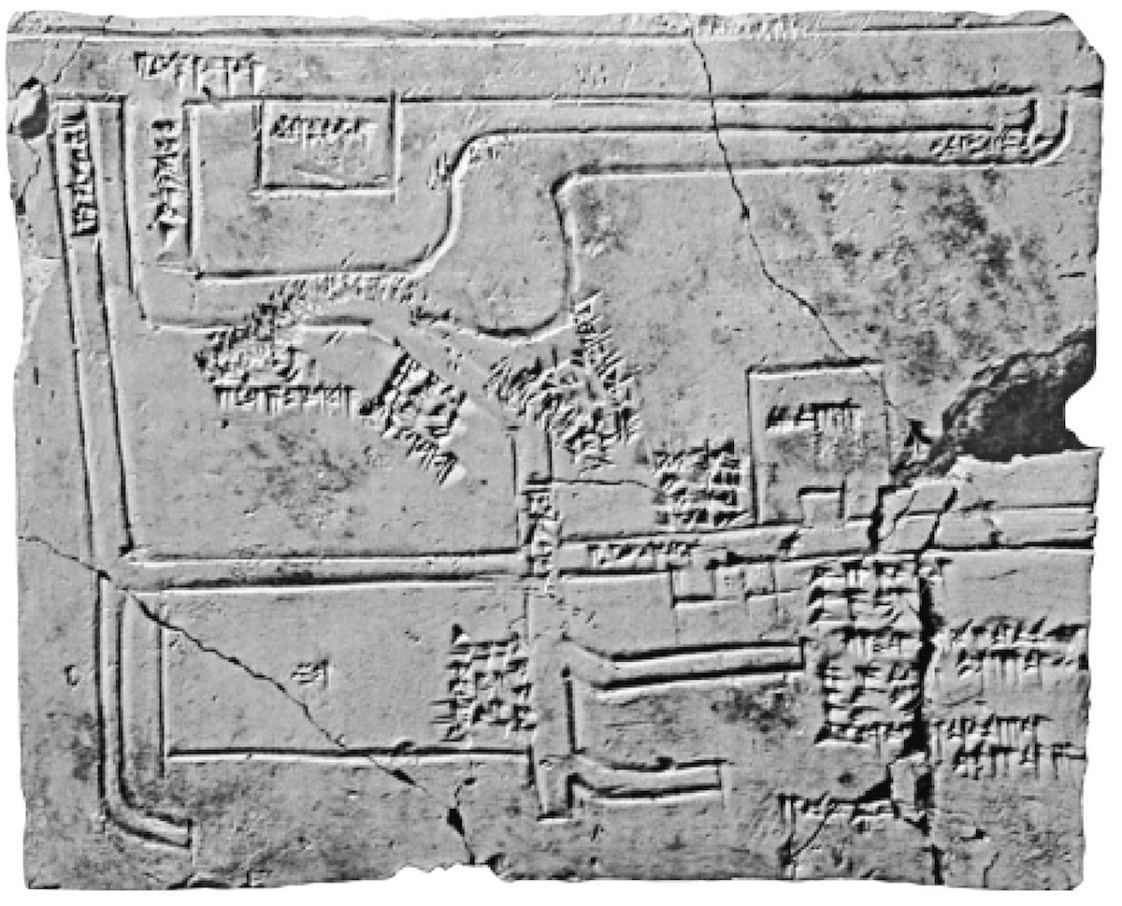

These three colloquia proved so successful that we decided to follow up by discussing the origins of money and accounting in 2002, at the British Museum, with the publication of Creating Economic Order.[16] This meeting established that money did not emerge out of individuals bartering goods to set prices. Administered initially as part of the accounting system developed in the temples and palaces of Sumer early in the third millennium BC, “money” was a price schedule to denominate payments of grain debts for sharecroppers on temple or palace lands, and for free citizens owing payments for water transport, draught animals, consumer goods such as beer or emergency borrowing, while silver debts were owed for long-distance trade with Cappadocia, Bahrain and the Iranian plateau.

In 2004 we held a fifth colloquium on labor in the ancient Near East and Mycenaean Greece, published as Labor in the Ancient World. This survey returned to our earlier discussions of the evolution of land tenure as part of a quid pro quo by which landholders were obliged to provide corvée labor and serve in the military.[17] Looking back to the Neolithic, it became apparent that labor on the vast ceremonial centers originally had to be voluntary, not based on slave labor. From Mesopotamia’s infrastructure to Egypt’s pyramids, great feasts and drinking parties were held upon the completion of major building projects, making them part of a basic communalistic socializing experience.

That final volume of our colloquia was published in 2015, taking account of Neolithic and Egyptian studies that were occurring rapidly as the field of prehistory was being rethought. Yet for the most part our research remained limited to Assyriologists, Egyptologists and other prehistorians.

By that time, widening recognition of the need for a debt writedown in the modern world led to a revival of interest in how societies through the ages have handled credit and debt. The most popular treatment of debt in its broad perspective was the anthropologist David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years (2011). We had corresponded over the years, and our collaboration has increased since publication of his work. The present book approaches debt from the perspective of early history and documentation from the ancient Near East.

What makes Western civilization “Western”?

Tension developed between the palace and local authorities and merchant-entrepreneurs seeking to pry away labor for themselves, by obliging it to work off debts. The rise and fall of society in Sumer’s Ur III period, and in Babylonia’s and Egypt’s “Intermediate Periods,” reflected the ebb and flow that has characterized all subsequent economies and is still shaping today’s world: the conflict between social constraints on predatory finance, and the attempt by a rentier class to gain control. Today’s era of collapsing central authority is strikingly like antiquity’s “Intermediate Periods,” marked by appropriation of land and public infrastructure, debt peonage and vast emigrations. These phenomena and the social tensions they cause seem timeless.

The origins of Western civilization are to be found in the way Bronze Age Sumer and Babylonia, Egypt and the Aegean broke down and gave way to their successors. In Greece, local Mycenaean palace managers disappear from records in 1200 BC, reappearing in the 8th century as basilae, concentrating land and hitherto palace wealth and authority in their own hands and that of their clans. The oligarchies that emerged as trade revived were overthrown in due course by populist “tyrants,” or managed a softer landing as in Athens under Solon. Nonetheless, credit and land were held much more in private hands than in the Near East. That is what has created constant tension between creditors and the indebted citizenry.

What made classical antiquity “modern” – and in the minds of many historians, “Western” – was the privatization of credit, land ownership and political power without the more or less regular Clean Slates that had been traditional in the Near East. Pseudo-Aristotle’s Constitution of Athens (XVI.2) reports that the 5th-century BC tyrant Peisistratus gained the support of many rural poor by paying off their debts himself. Cicero (de Rep. II. 21) likewise describes the legendary Roman king Servius as having strengthened his position by paying off the obligations of local debtors. Diodorus says much the same thing of Servius’s predecessor Tarquin.[18] But in the end it was the large landowners and creditors who became wealthy enough to decide elections.

The concept of private property permitting creditors to expropriate mortgage debtors that is widely accepted today, already throughout antiquity led to a cry for debt cancellation – as late as Kings Agis V and Cleomenes III in Sparta (late 3rd century BC) and Mithridates in his three wars against Rome (88 to 63 BC).

The absence of royal, religious or civic debt amnesties made classical Greece and Rome different from the Bronze Age Near East. Our own civilization inherited Rome’s pro-creditor legal principles that helped the oligarchy impoverish its citizenry.

A legacy of financial instability

Babylonian scribal students were trained already c. 2000 BC in the mathematics of compound interest. Their school exercises asked them to calculate how long it took a debt at interest of 1⁄60th per month to double. The answer is 60 months: five years. How long to quadruple? Ten years. How long to multiply 64 times? Thirty years. It must have been obvious that no economy can grow in keeping with this rate of increase.

Babylonian training exercises grasped that herds and production grow in S-curves, tapering off – while debts mount up, ever growing at interest. This tendency for debts to accrue faster than the economy can grow is missing from today’s academic curriculum. Mainstream economic models assume that financial trends are self-correcting to restore balance. The reality is that debts growing at compound interest tend to polarize and impoverish economies, if not corrected from “outside” the economy. Sumerians, Babylonians and their Near Eastern neighbors recognized the need for this action.

Today’s “free enterprise” model-builders deny that debt writeoffs are needed. Modern ideology endorses chronic indebtedness as normal, despite debt service drying up the internal market and forcing a widening range of debtors into financial dependency.

In all epochs a basic maxim applies: Debts that can’t be paid won’t be paid. What always is at issue is just how they won’t be paid. If they are not written down, they will become a lever for creditors to pry away property and income from debtors – in practice, from the economy and community at large.

At the outset of recorded history, Bronze Age rulers relinquished fiscal claims and restored liberty from permanent debt. That prevented a creditor oligarchy from emerging to the extent that occurred in classical antiquity. Today’s world is still living in the wake of the Roman Empire’s creditor-oriented laws and the economic polarization that ensued.

See ENDNOTES: Archaic Economies versus Modern Preconceptions

The Major Themes of this Book

All economies tend to polarize between creditors and debtors if not counteracted by writing down debts in line with the ability to pay without widespread default and forfeiture of land and property. Failure to write down debt arrears creates a creditor class at the top of an increasingly steep economic pyramid, reducing much of the population to debt clientage or worse.

1. Charging interest on debts was innovated in a particular part of the world (Sumer, in southern Mesopotamia) some time in the Early Bronze Age, c. 3200–2500 BC. No trace of interest-bearing debt is found in pristine anthropological gift exchange, or even in the Linear B records of Mycenaean Greece 1600–1200 BC. The practice diffused westward to the Aegean and Mediterranean c. 750 BC.

2. A major task of Babylonian and other Mesopotamian rulers upon taking the throne was to restore economic balance by cancelling agrarian personal debts, liberating bondservants and reversing land forfeitures for citizens holding self-support land.

3. The easiest debts for rulers to remit were those owed to the palace, temples and their collectors or professional guilds. But by the end of the third millennium BC, wealthy traders and other creditors were engaging in rural usury as a sideline to their entrepreneurial activities. Enforcing collection of such debts owed to the palace, its bureaucracy and private lenders would have disenfranchised the land-tenured citizen infantry and lost the corvée labor service and military duties of debtors reduced to bondage.

4. Debt cancellations were not radical, nor were they “reforms.” They were the traditional means to prevent widespread debt bondage and land foreclosures. Bronze Age rulers enabled economic relations to start afresh and in financial balance upon taking the throne and when needed in times of crop failure or economic distress. There was no faith in inherent automatic tendencies (what today is called “market equilibrium”) to ensure economic growth. Rulers recognized that if they let debt arrears mount up, their societies would veer out of balance, creating an oligarchy that would impoverish the citizen-army and drive populations to flee the land.

5. Palace collectors and merchant entrepreneurs acted increasingly as creditors on their own account. A political tug of war ensued as nomadic tribesmen conquered southern Mesopotamia and took over temples and turned them into exploitative vehicles while trying to resist customary checks on the corrosive effects of debt.

6. Classical antiquity replaced the cyclical idea of time and social renewal with that of linear time. Economic polarization became irreversible, not merely temporary. Aristocracies overthrew rulers and ended the tradition of restoring liberty from debt bondage. This brought “modern” land ownership into being as debtors forfeited their land tenure rights or fell into bondage with little hope of recovering their free status.

7. Without Clean Slates, creditor oligarchies appropriated most of the land and reduced much of the population to bondage. Creditors translated their economic gains into political power, casting off the fiscal obligations that originally were attached to land tenure rights. The burden of debt and its mounting interest charges led to the foreclosure of land as the basic means of self-support and hence the loss of the debtor’s liberty.

8. Livy, Plutarch and other Roman historians described classical antiquity as being destroyed mainly by creditors using interest-bearing debt to impoverish and disenfranchise the population. Barbarians always stood at the gates, but only as societies weakened internally were their invasions successful. The invasions that ended the fading Roman Empire were anticlimactic. In the end, the only debts that Emperor Hadrian could annul with his fiscal amnesty were Rome’s tax records, which he burned in 119 AD – tax debts owed to the palace, not debts to the creditor oligarchy that had gained control of Rome’s land.

9. Archaic traditions of restoring order, originally legally enforceable, were given an otherworldly eschatological meaning as the social order collapsed under the burden of debt. Losing hope for secular revival, antiquity felt itself to be living in the End Time.

10. The Qumran scroll 11QMelchezedek wove together Biblical texts concerning debt cancellations with apocalyptic texts about the Day of Judgment. Although many of Jesus’ sermons used images and analogies associated with debt, the idea of redemption and forgiveness was spiritualized to the point where it lost its basis in fiscal and debt amnesties that had released debtors from bondage.

11. Byzantine rulers revived the Near Eastern practice of returning land tenure to smallholders, nullifying foreclosures, “gifts” and even outright purchases as constituting stealth takeovers by the wealthy. Takeovers via antichresis (taking the land as ostensibly temporary collateral to pay the interest due) also were annulled.

12. The common policy denominator spanning Bronze Age Mesopotamia and the Byzantine Empire was the conflict between central rulers acting to restore land to smallholders so as to maintain royal tax revenue and a land-tenured military force, and wealthy or powerful families seeking to concentrate land in their own hands, denying this usufruct to the palace. When royal power to preserve widespread land tenure waned under assertive oligarchies, the result was economic shrinkage and ultimate collapse.

Part I:

Overview

1.

Babylonian Perspective on Liberty and Economic Order

Modern American society retains many iconographic references that can be traced back to ancient Babylonia. Our nation’s two most familiar symbols of freedom, the Statue of Liberty and the Liberty Bell, recall vestiges of an ancient tradition that has been all but lost since imperial Roman times: liberty from bondage and from the threat of losing one’s home, land and means of livelihood through debt.

To a visitor from Hammurabi’s Babylon, the Statue of Liberty might evoke the royal iconography of the important ritual over which rulers presided: restoring liberty from debt. The earliest known reference to such a ritual appears in a legal text from the 18th century BC. A farmer claims that he does not have to pay a crop debt because the ruler, quite likely Hammurabi (who ruled for 42 years, 1792–1750 BC), has “raised high the Golden Torch” to signal the annulling of agrarian debts and related personal “barley” obligations.[19]

Unlike today’s business cycle economists, Bronze Age societies had no faith in the spontaneous equilibrating forces of modern-style market mechanisms, nor did they believe that all debts should be paid. Their laws recognized that floods and droughts, military conflict or other causes prevented cultivators from harvesting enough to pay the debts they had run up during the crop year. Palaces and temples were the major creditors, and their guiding objective was to maintain a free citizenry to serve in the military and provide the seasonal corvée labor duties attached to land tenure. Instead of letting “the market” resolve matters in favor of foreclosing creditors, rulers saw that if cultivators had to work off their debts to private creditors, they would not be available to perform their public corvée work duties, not to mention fight in the army.

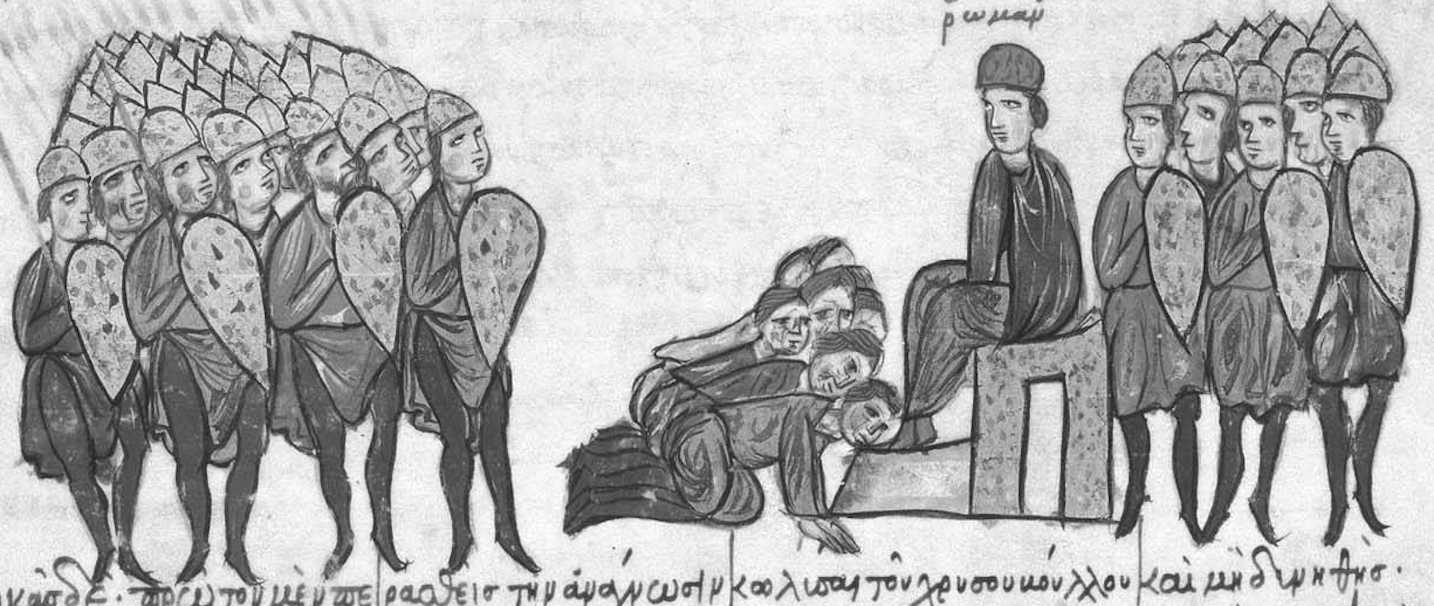

By liberating distressed individuals who had fallen into debt bondage, and returning to cultivators the lands they had forfeited for debt or sold under economic duress, these royal acts maintained a free peasantry willing to fight for its lands and work on public building projects and canals. Cuneiform references to such debt cancellations have been excavated in Lagash, Assur, Isin, Larsa, Babylon and other Near Eastern cities as far west as Asia Minor. By clearing away the buildup of personal debts, rulers saved society from the social chaos that would have resulted from personal insolvency, debt bondage and military defection.

The Babylonian ruler’s ceremonial gesture of holding aloft a flame to signal mīšarum, clearing the slate of debts, seems to have marked the transition to a new reign by the new ruler upon the death of his predecessor after the period of mourning had ended. A loan contract from year 9 of Hammurabi’s father, Sin-muballi† (1803 BC), specifies that the loan was “after the king raised high the golden torch,” indicating that it was not subject to that northern ruler’s mīšarum act.

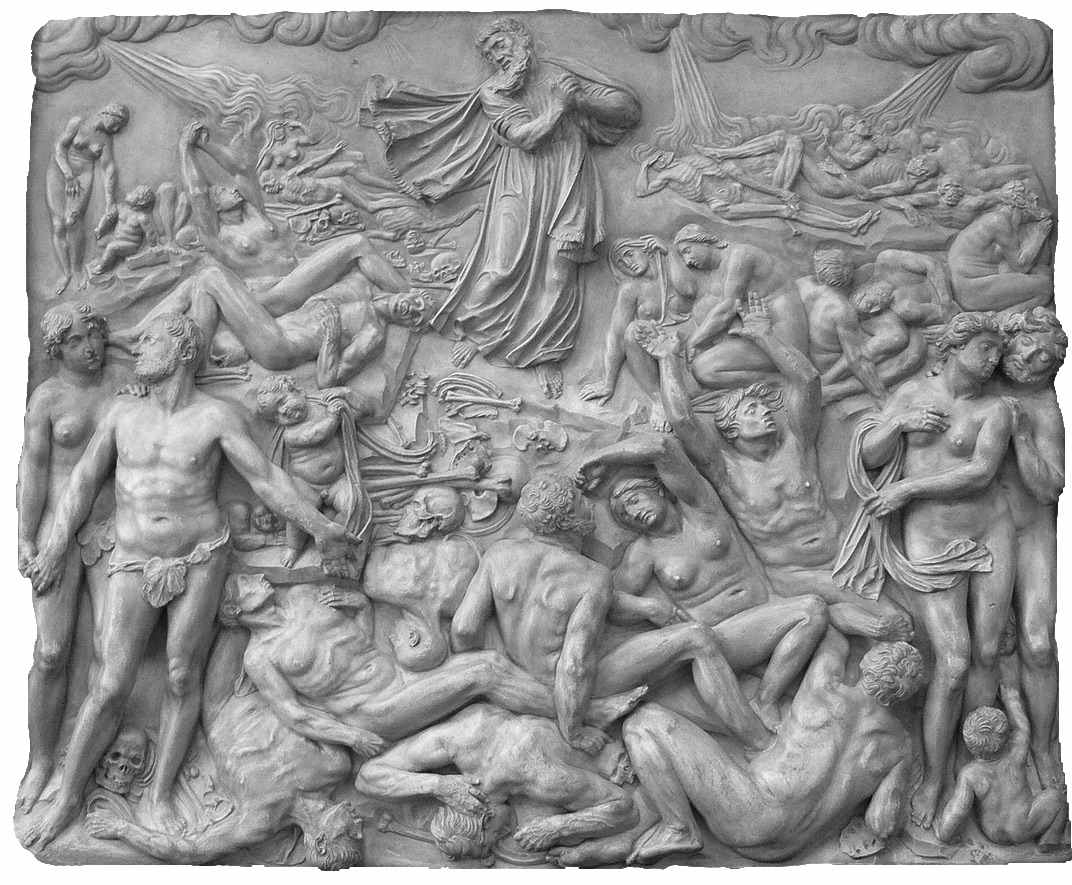

Figure 1 (below): Liberty Bell, Philadelphia, referring to Leviticus 25.

“‘I Am the Sun of Babylon’ appears in the Prologue to Hammurabi’s laws. Earlier, Shulgi proclaimed himself ‘Sun of his land,’ or ‘faithful god, sun of his land.’ Shu-ilishu of Isin called himself ‘Sun of Sumer.’”[20] Casting themselves in the image of Babylonia’s sun god of justice – Shamash, Illuminator of Darkness – rulers restored order and equity by cancelling back taxes, crop-rent arrears and other consumer debts.

A long imagery of social cosmology was at work extending down through the Hellenistic 2nd and 1st centuries BC. As Arnold Toynbee summarized this imagery, “the Sun stood for justice. The Sun distributes his light and warmth impartially. He bestows them on the poor just as generously as on the rich. They are blessings in which all living creatures alike have an equal share, and one human being cannot be deprived of them by another. All are at liberty to share in the Sun’s gifts, so he stands, not only for justice, but for the liberty that justice demands.” For Hellenistic Stoic philosophers this solar principle was Helios Eleutherios.”[21] The Statue of Liberty’s base is inscribed with lines from Emma Lazarus’s poem “The New Colossus”: “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.” This sentiment is kindred to Hammurabi’s pledge in the epilogue to his famous laws, inscribed on imported diorite stone for all the public to see – and to be copied by scribal students for over a thousand years:

… that the strong might not oppress the weak,

that justice might be dealt to the orphan and widow …

I write my precious words on my stele …

To give justice to the oppressed.[22]

Should our Babylonian visitor proceed to the Liberty Bell in Philadelphia, he would find further vestiges of the idea of absolution from debt bondage. The bell is inscribed with a quotation from Leviticus 25.10: “Proclaim liberty throughout all the land, and to all the inhabitants thereof.” The full verse refers to freedom from debt bondage when it exhorts the Israelites to “hallow the fiftieth year, and proclaim liberty throughout all the land and to all the inhabitants thereof; it shall be a Jubilee unto you; and ye shall return every man unto his family” (and also every woman, child and house slave who had been pledged). Lands were restored to their traditional holders clear of debt encumbrances. Sounding the ram’s horn on the Day of Atonement of this fiftieth year signaled the renewal of economic order and equity by undoing the corrosive effects of indebtedness that had built up since the last Jubilee.

The Hebrew word translated as “liberty” in the Leviticus text is deror. It is cognate to andurārum in Akkadian, a related Semitic language of early Babylonia. The root meaning of both words is to move freely like running water – in this case like bondservants liberated to rejoin their families. As early as 2400 BC the Sumerian term amargi signified the return to the mother. Similar terms existed in most Near Eastern languages of the period: níg-si-sá in Sumerian, mīšarum in the Akkadian language used in Babylonia, and šudūtu in Hurrian-speaking Nuzi upstream along the Euphrates.[23]

Until the 1970s translators construed these terms as meaning freedom in an abstract sense. The idea of creditors not being paid seemed so radical that academics doubted that debts could really have been cancelled without deranging social life, or perhaps triggering a political backlash by the well-to-do against rulers annulling their claims for payment.

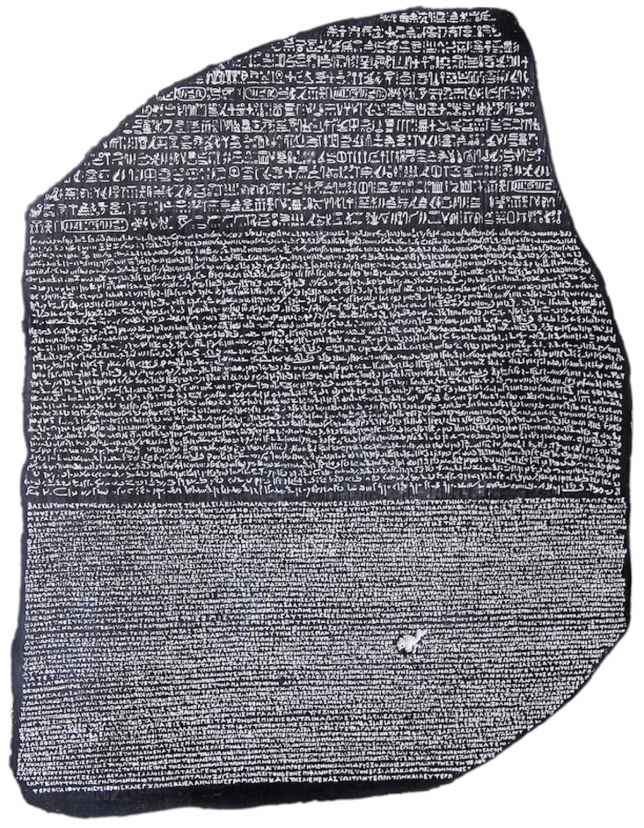

What helped settle matters was the Rosetta stone. Nearly everyone knows that this trilingual Egyptian inscription provided the key for reading and understanding hieroglyphics after it was dug up by Napoleon’s troops in 1799. What is almost always overlooked is what the stone reports. It was a debt amnesty by a young ruler from the Ptolemaic dynasty (a lineage founded by one of Alexander the Great’s generals in 314 BC). The stone’s inscription commemorates the cancellation of back taxes and other debts by the 13-year old Ptolemy V Epiphanes in 197 BC, evidently indoctrinated by Egypt’s priesthood, into the ways of emulating former pharaohs.

In one language after another, initial doubts have been dispelled: The economic liberty referred to was an amnesty on arrears of back taxes and other personal debts. Rulers cancelled these arrears to liberate citizens and their family members pledged to creditors for debt, and to restore the customary land-tenure rights that had been forfeited to creditors. There can be no doubt that these edicts were implemented. Over the course of Hammurabi’s Babylonian dynasty (1894–1600 BC) they grew into quite elaborate promulgations, capped by his great-great-grandson Ammisaduqa in 1646 BC.

Proclamation of these clean slates became so central a royal function that the phrase “to issue a “royal edict” (ṣimdat šarrim) usually referred specifically to a debt cancellation.[24] The act typically was commemorated in the year-name for the ruler’s second year, reflecting what they had done in their initial year upon taking the throne. These texts have been excavated mainly from temple foundations, where Urukagina (2352–2342 BC) and Gudea of Lagash (c. 2150) buried them on the occasion of inaugurating temples or celebrating their coronation. In 1792 BC, Hammurabi’s “second” year commemorated this initial coronation act, repeated when he celebrated his 30th anniversary on the throne in 1762 after defeating Rim-Sin of Larsa, as well as when he responded to economic or military pressures to cancel debts in 1780 and 1771 BC.

By the first millennium BC, however, kings had lost the power to overrule local aristocracies. Where they survived, they ruled on behalf of the wealthy. From Solomon and his son Rehoboam through Ahab and most subsequent rulers, the Bible depicts most Israelite kings as burdening the people with taxes, not freeing them from debts or palace demands. That is why the Biblical prophets shifted the moral center of lawgiving out of the hands of kings, making debt cancellation and land reform automatic and obligatory as a sacred covenant under Mosaic Law, handed down by the Lord.

Today’s readers of the Bible tend to skim over the Covenant Code of Exodus, the septennial šemittah year of release in Deuteronomy and the Jubilee Year of Leviticus as if they were idealistic fine print. But to the Biblical compilers they formed the core of righteousness. Liberated from bondage to Egyptians (apparently designated as a mythic analogy to the oppressive Judean oligarchy), the Israelites are represented as holding their land in trust as the Lord’s gift to support a free population, never again to be reduced to debt bondage and lose their land to foreclosing creditors, or to sell the land irrevocably under economic distress. “Land must not be sold in perpetuity, for the land belongs to me and you are only strangers and guests. You will allow a right of redemption on all your landed property, and restore it to its customary cultivators every fifty years” (Leviticus 25: 23–28).

The broad theme of this book is how the modern concept of economic liberty has stood the original meaning of liberty on its head. Today’s pro-creditor “market principle” favoring financial claims by holding that all debts must be paid, reverses the archaic sanctity of releasing indentured debt pledges and property from debt bondage. The idea of linear progress, in the form of irreversible debt and property transfers, has replaced the Bronze Age tradition of cyclical renewal.

Central to any discussion of this inversion is the fact that Mesopotamia’s palaces and temples were the major creditors at the beginning of recorded history. To enable them to perform their designated functions, communities endowed them with land and dependent labor. Neither temples nor palaces borrowed from private creditors (although their functionaries and entrepreneurs acting for them did). Nowhere in antiquity do we find governments becoming chronic debtors. Debts were owed to them, not by them.

Today’s world is the opposite. When the U.S. Congress discusses ways to reduce the federal budget deficit, the most untouchable category of expenditures is payment to bondholders on the public debt. The same is true for Third World countries negotiating with banks and the International Monetary Fund – creating the recent debt-ridden austerity and economic collapse imposed on Greece.

A Babylonian would be more open than most modern economists to recognizing the corrosive impact of debt. There was no faith in “automatic” adjustment mechanisms guiding economies to be able to carry their debts. Economic balance had to be imposed from “above” the market Ancient history provides a series of case studies illustrating how annulling an overbearing debt overhead renewed economic growth and stability rather than disrupting it. From the Biblical prophets to Roman Stoic historians a central theme was the accusation that what tore their society apart was the failure to cancel debts.

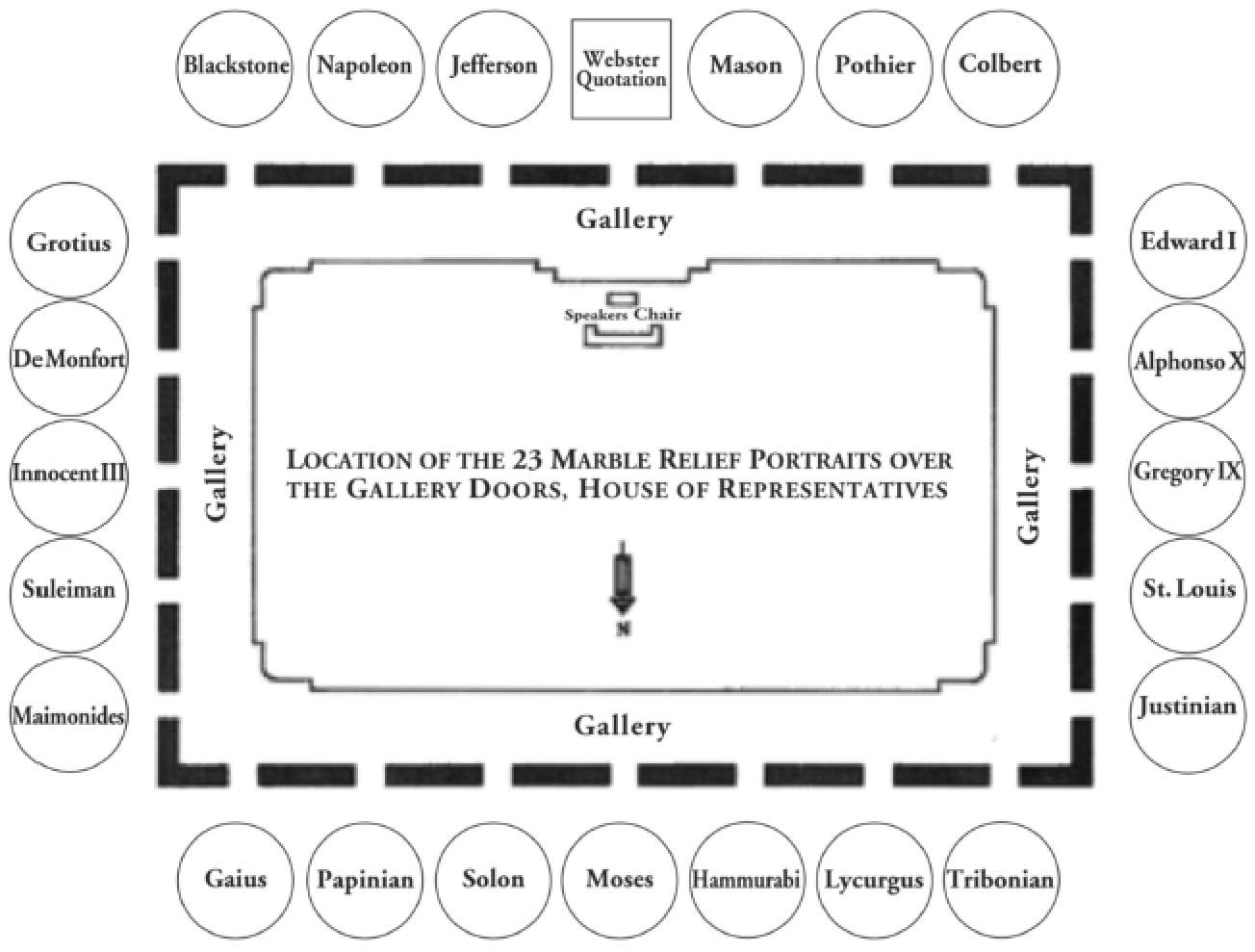

The legacy of lawgivers proclaiming clean slates is commemorated at the entrance to the United States House of Representatives. Grouped around Moses in the center, with Hammurabi on his right, are “23 marble relief portraits of ‘historical figures noted for their work in establishing the principles that underlie American law.’”[25] Hammurabi promulgated debt cancellations by royal edict (depicted as showing his cuneiform laws to the sun-god Shamash). But Moses – in the later Biblical epoch when kings no longer promoted widespread liberty – received his body of law directly from the Lord. The Jubilee Year and related laws were taken out of the hands of worldly rulers and placed at the center of Judaic religion.

Among these stone portraits of lawgivers is Lycurgus, whom Plutarch describes as annulling Sparta’s debts and even abolishing gold and silver money, replacing it with iron whose value was controlled by the state, not the wealthy. The other portrait from Greece is of Solon, who lay the groundwork for Athenian democracy by freeing the hektemoroi debt serfs and ending debt bondage in 594 BC.

Figure 2 (below): House of Representatives, location of the portraits of 23 historic lawgivers.

The sponsorship of financial Clean Slates by these lawgivers is the opposite of the principles governing today’s economies. According to modern economic orthodoxy, cancelling personal debts should have led to financial chaos instead of saving the economy from chaos. The reality is that Mesopotamia’s takeoff could not have been sustained if its rulers had adopted today’s sanctity of debt.

We are living in the kind of market economy that favors ambitious tycoons, corporate raiders and emperors of finance indulging in what classical philosophy called hubris. This term meant economic egotism and selfishness in ways that were injurious to others, above all the injurious and predatory greed of creditors against debtors. It was the role of goddesses from Mesopotamia to classical Greece to protect the weak and poor by punishing hubris. Today, on top of the Capitol is a Statue of Freedom. She is female, but the planners would have had no memory of the role that Nanshe of Lagash played, or even Nemesis in Greece. Like the ancient male gods of justice, from Hammurabi’s Sun-God Shamash to the Mosaic Lord, these consorts have become a lost tradition. All that remains in the public mind are myths and images whose original meaning has been forgotten, because their tradition is alien to our modern ideology and the way that our major religions have evolved.

See ENDNOTES Chapter 1: A Babylonian Perspective on Liberty and Economic Order

2.

Jesus’s First Sermon and the Tradition of Debt Amnesty

In the first reported sermon Jesus delivered upon returning to his native Nazareth (Luke 4:16 ff.), he unrolled the scroll of Isaiah and announced his mission “to restore the Year of Our Lord.” Until recently the meaning of this phrase was not recognized as referring specifically to the Jubilee Year. But breakthroughs in cuneiform research and a key Qumran scroll provide a direct link to that tradition. This linkage provides the basis for understanding how early Christianity emerged in an epoch so impoverished by debt and the threat of bondage that it was called the End Time.

Jesus was both more revolutionary and more conservative than was earlier recognized. He was politically revolutionary in threatening Judaic creditors, and behind them the Pharisees who had rationalized their rights against debtors. Luke 16: 13–15 describes them as “loving money” and “sneering” at Jesus’s message that “You cannot serve both God and Money/Mammon.”[26] The leading rabbinical school in an age when creditor power was gaining dominance throughout the ancient world, the Pharisees followed the teachings of Hillel. Now credited as a founder of rabbinical Judaism, he sponsored the prosbul clause in which creditors obliged their clients to waive their rights to have their debts cancelled in the Jubilee Year.

Jesus’s call for a Jubilee Year was conservative in resurrecting the economic ideal central to Mosaic Law: widespread annulment of personal debts. This ideal remains so alien to our modern way of thinking that his sermons are usually interpreted in a broad compassionate sense of urging personal charity toward one’s own debtors and the poor in general. There is a reluctance to focus on the creditor oligarchy that Jesus (and many of his contemporary Romans) blamed for the epoch’s deepening poverty.